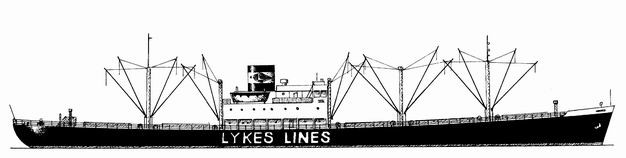

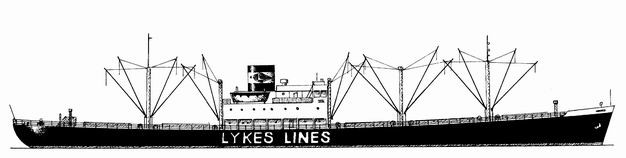

SS JOHN LYKES

TRANSPORTED THE 97TH ENGINEERS TO NEW GUINEA,

10 March–9 April 1944

Going Home [after dropping off the Engineers]

Soon after the euphoria of liberation, the internees thoughts turned to going home. Repatriation started almost immediately, with the sickest of the military POWs from Bilibid going first. Then on February 12, 1945, while the battle of Manila still raged, the Army nurses in Santo Tomas departed, followed by a large group of civilians on February 23. Those early repatriations occurred from a temporary airfield in North Manila and the people were flown to Leyte to board ships. Finally the Port of Manila was declared safe, and the first repatriation ship from there was the SS John Lykes, departing on April 2, 1945. This is the story of that voyage as told by Angus Lorenzen.

We finally received notice that we were on the next repatriation ship, and assembled with our battered suitcases in the plaza early on the morning of April 2. As our bus drove through the main gate, I looked back to see Santo Tomas for the last time for more than 50 years.

We turned towards the Pasig River, seeing the fruits of the Battle of Manila. The buildings were shell pocked and burned-out shells, and bridges were wreckage of twisted steel. We crossed on a pontoon bridge and passed what was left of the Intramuros, the once massive walls reduced to rubble and the inside a sea of devastation with only the shell of a cathedral showing above the rubble.

Turning away from the destruction, we drove onto a pier and saw a large gray ship. The S.S. John Lykes was leased to the Army as a troop transport. By today’s standards, she was relatively small - 418-feet long and 5,028 gross tons, configured to carry 1,288 troops. It was similar to a Victory ship, except with a higher top speed, and armed with two 3-inch guns forward, a 4-inch gun aft, and several 20-millimeter guns.

I was assigned to one of the two forward holds with GIs and civilian men, while my mother and sister were in the aft hold with all of the women. On board were about 500 ex-prisoners from Santo Tomas and an equivalent number of GIs, not a full load; but still crowded.

We sailed in the late afternoon, twisting and turning along a narrow passage blasted between the hulks of sunken ships in Manila Bay. That evening, we passed Corregidor and joined a convoy being assembled for the voyage to America.

Our convoy had about 50 ships neatly aligned in parallel columns, with a screen of destroyer escorts patrolling around the edges. The speed was abysmally slow, no more than 6 knots. Strangely, we were sailing south, rather than northeast, where America lay. Even though the Japanese fleet had largely been destroyed in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, many surface warships survived and submarines still harried Allied shipping in the western Pacific. Our course would take us through the Philippine Islands, across the equator to New Guinea, then across the Pacific to Hawaii and the West Coast.

On our first morning at sea, there was an abandon-ship drill. If the ship was damaged or sinking, we were to report to our assigned emergency stations wearing our kapok life jackets, and remain there until ordered to abandon ship. When that order came, we were to jump overboard, and life rafts stowed in various places on the ship would be released into the water, which we should board. The explanation seemed so straightforward and easy that there was no reason to worry. Nothing was said about floating or burning oil and the difficulties we might encounter if the ship was still under attack.

We soon developed a daily routine for the month at sea. Everyone staked out territory on deck, where we slept, braving the tropical showers to avoid the 5-high bunks and the stifling heat in the holds. We had three square meals a day served mess-hall style, the GIs sharing mess duty while we civilians freeloaded. But the most important event of the day was at noon when a news report was read over the ship’s public address system. In Europe, Germany’s defenses were collapsing under the Allied advances on Berlin.

We crossed the equator without the traditional ceremony, but did received a certificate attesting to the fact that we’d met King Neptune’s requirements and were now qualified members of the court. We received a similar certificate later when we crossed the International Date Line.

The ship docked and resupplied at New Hollandia, then started the long voyage across the trackless Pacific while the destroyer escorts tightened up the formation. All ships were directed to hold a live fire practice, and for an hour, every ship was firing all of its armament, with our Navy gun crews enthusiastically participating. The sound reverberating off the steel plates of the ship was deafening, far worse than artillery during the battle of Manila.

Half way to Hawaii our ship required more rations, and a supply ship came alongside about 100 feet from us. Lines were passed across the open water, and crates were swung across and quickly stored below. Unfortunately, one crate was mishandled and broke apart, spewing Hershey chocolate bars across the deck, which quickly and miraculously disappeared, leaving only grinning faces with smears of brown.

On April 14 we all gathered on our favorite perches for the noon report. Expecting to hear more good news about the advance on Berlin, the first bulletin was a complete shock. President Roosevelt had died the previous day in Warm Springs, Georgia. The newsreader paused, and there was a total silence, then someone sobbed, and all around me were these tough GIs with tears streaming down their faces. The people loved this jaunty president who had led the country out of the Great Depression and directed the armed forces as they smashed the German and Japanese war machinery.

A few days later, another tragedy struck. A small child died, weakened by the poor nutrition in Santo Tomas. With no place to keep the remains, the child was given a burial at sea according to maritime tradition.

Our convoy broke up when we reached Hawaii, and we were on our own for the last leg. The days were now getting cooler and it was no longer comfortable to sleep out on the deck, while the temperature in the hold was more pleasant.

Sleeping soundly one night, I was jolted awake by the raucous sound of the alarm klaxon warning everyone to go to the abandon ship stations. The GIs in the bunks around me complained that it was just a nuisance drill, and decided that they’d skip it and go back to sleep. I figured they knew what they were doing, and skipped the drill also. The sound of running and shouts coming from above, followed by slamming and toggling of watertight doors, kept me awake until I finally got to sleep in the eerie quiet.

Unconcerned that I’d skipped the drill, I sauntered onto the deck in the morning, only to discover that it was not a drill! During the night, the ship’s watch had seen a submarine on the surface that did not respond to the recognition signal. The gun crews tracked the submarine, waiting either for the proper coded reply or for the order to fire and sink it. It was on a course that was the reverse of ours, and we were approaching bow-on. And then it quietly passed our port side and slowly slipped into the dark astern. The submarine was never explained, and we’ll never know whether it was friend or foe.

In the predawn hours of May 2 everyone aboard ship assembled on the deck. In the dim light, we could see low hills in the distance. America at last! The ship slowed to a frustratingly imperceptible speed. After 31 days on the John Lykes, we were all impatient to get past the last 3 or 4 miles to our dock.

A band was on the dock playing patriotic favorites as we moored, and a crowd of people stood nearby waving and shouting. The GIs departed first, and we boarded buses to take us to a reception center at the Elk’s Club in Los Angeles.

When we entered the hall, friends and relatives rushed to meet loved ones, and hugs, kisses, and crying followed. But we didn’t expect anyone, and only wanted to know what we were to do next. A tall soldier started walking over to us saying, “Elsie? Elsie is that you?” And then he rushed to my mother and hugged her, finally turning to hug my sister, then me. It was my brother, who I hadn’t seen since he left for college in Shanghai before the war started. It was a testament to how much we had changed, especially my mother, that he had made that first tentative question when he first saw us. He too had changed, seeming taller, more mature, and very handsome in his Army uniform.

In the days that followed there was a rush to exchange stories, but it was several days before we learned of John’s adventures with the Chinese guerillas and the Flying Tigers. He was now stationed in Washington D.C., and also told us that after being repatriated in 1943, my father was back in China serving with the OSS.

Right now, though, the first order of business was lunch. We drove to a nearby restaurant, where for the first time since entering Santo Tomas, we were be able to choose from a menu. It was overwhelming, until I saw the word, “hamburger”, and my choice was made as I remembered the loving detail with which the GIs described this delicacy. Combined with a pile of greasy French fries it was pure heaven, and we knew we were back in the heart of civilization.

Papua New Guinea Stamp:

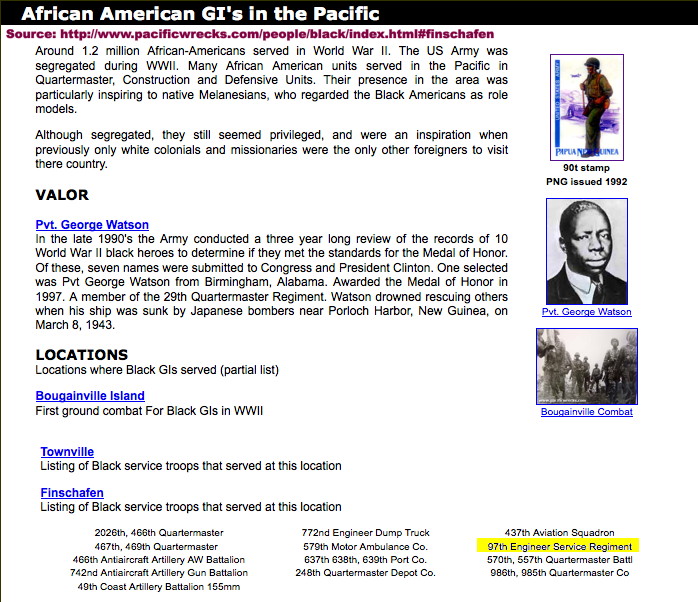

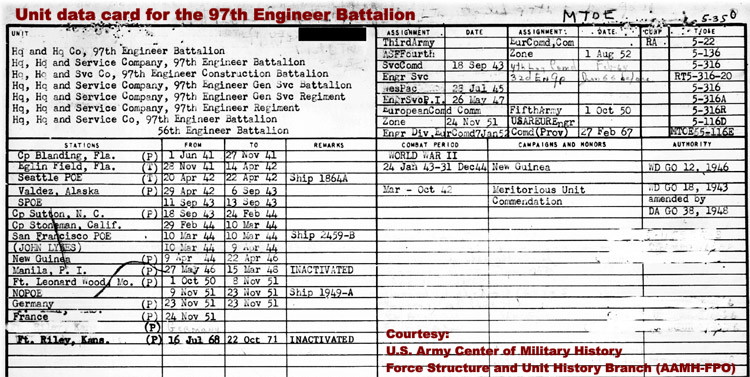

97th Engineer Regiment: Service in New Guinea

Very little information surfaced regarding activities of the 97th Engineer Service Regiment, but we know they were based at:

Finschafen

The unit's records are not consistent, in that the data card on file with the US Army Center of History incorrectly show their combat period as between 24 January 1943 and 31 December 1944. However, the left side of that same form (see Data Card below) shows they were in New Guinea from 9 April 1944 until 22 April 1946, taken there by the SS John Lykes.