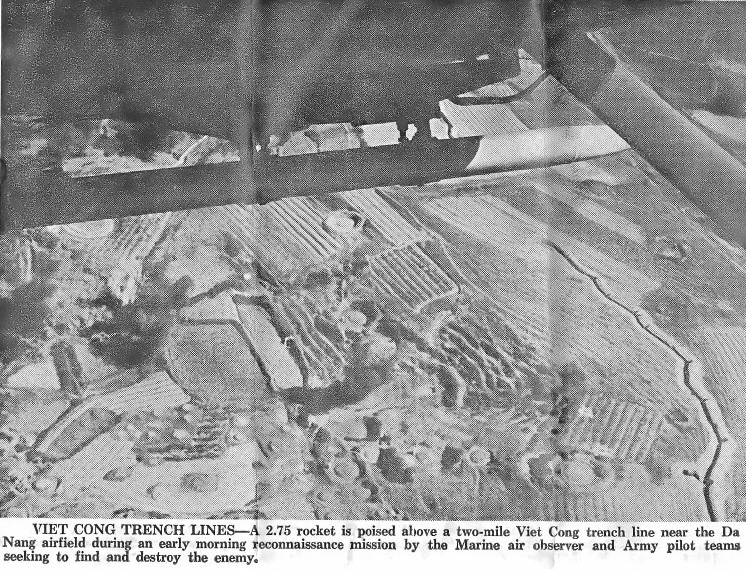

THE ‘CAT KILLERS’ PATROL THE SKY

Story and Photographs by

WO Jim Smith, CIB

[SEA TIGER Vol. 2 No. 4, III MAF, Vietnam, February 1, 1966, page4–5]

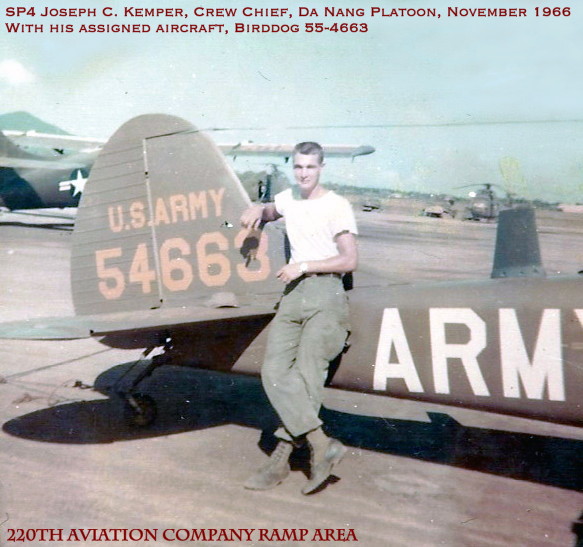

Tracscribed by Jack Bentley and republished by Donald M. Ricks, CATCOM Editor,

from material courtesy of Joseph E. Kemper, Catkiller Crew Chief, Da Nang, 1965–66

DA NANG—They call themselves “Cat Killers”. Actually they are a small, closely–knit team of “heroic fools” doing a dangerous job in a war against communist brutality.

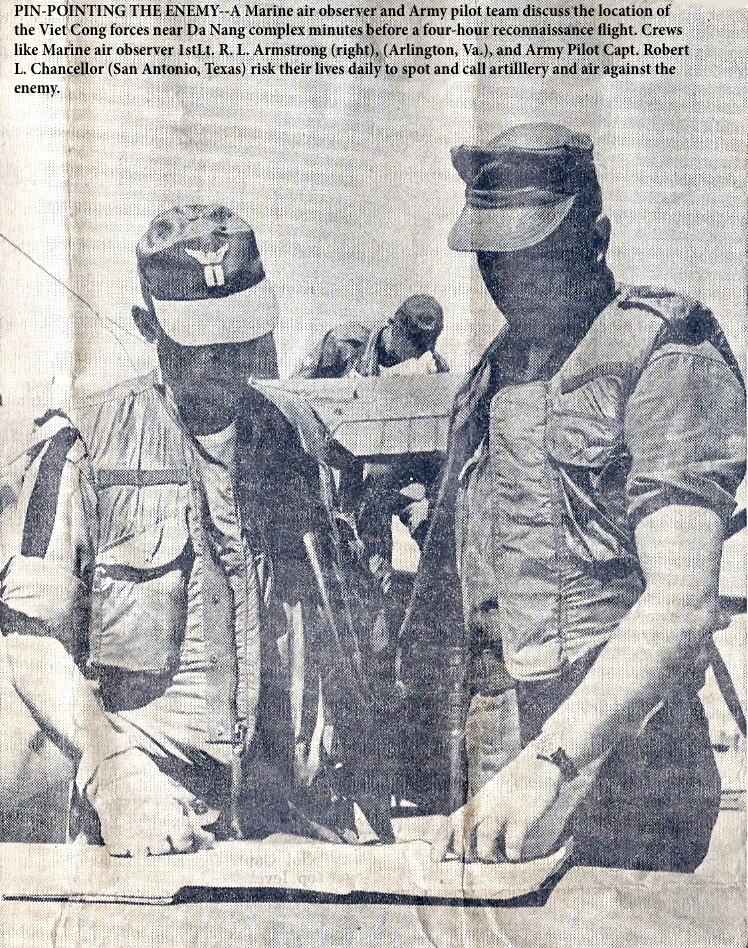

The Cat killers are nine U.S. Army pilots who fly nine U.S. Marine aerial observers (AO) over More than 800 square miles of Vietnam looking for Viet Cong.

To read their mission one would say it’s quite simple—a piece of cake. The men of the 3d Marine Division Aerial Observer Team and the Army’s 220th Aviation Company also believe their task is a “piece of cake.”

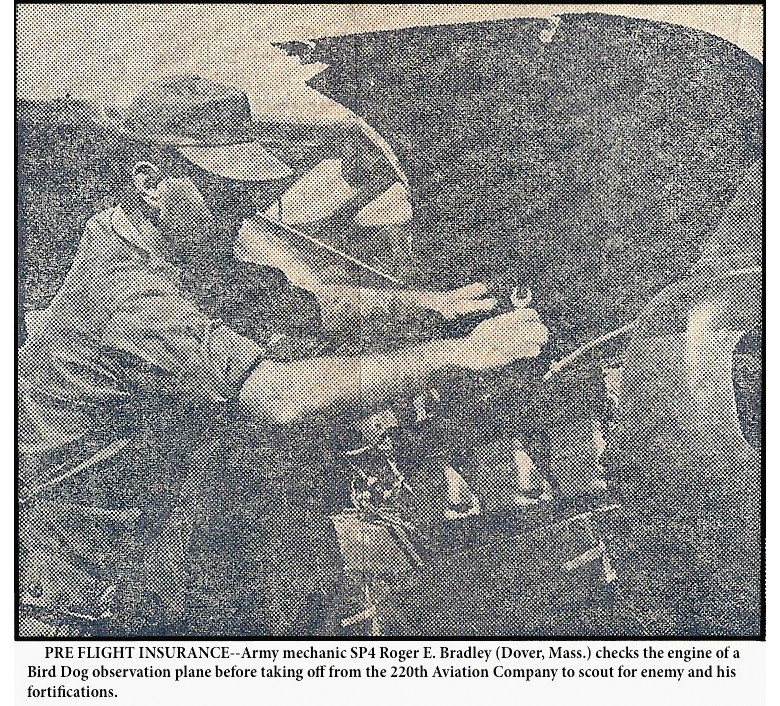

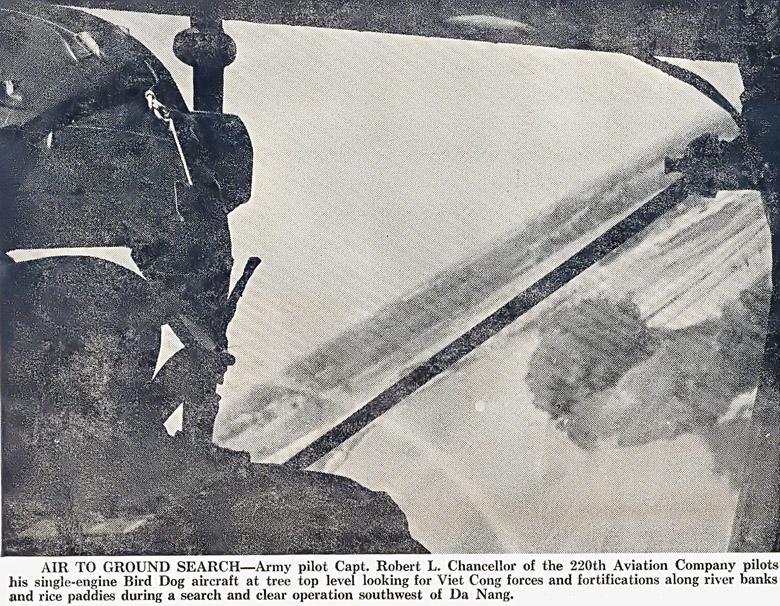

But to an observer riding in the back seat of the tiny, single–engine O1D observation plane, the Mission is without a doubt the most dangerous of all in the Republic of Vietnam.

How close is too close to the ground when a pilot/observer team brings home tree branches from a four–hour mission of searching river beds, hamlets, villages, mountains and rice paddies for a sighting of the enemy. How close is too close when one pilot or observer is shot five or six times while calling in artillery fire on the Viet Cong who are centralizing for a push against our military installations.

Marine Captain James F Baier (Green Spring, Wisc.), assistant 3d Marine Division, aerial Observer, and veteran of 135 missions over Vietnam, described one particular flight as dangerous “when we have to mark hostile enemy positions with smoke grenades.” He added, however, “There’s no other way to accurately pin–point the enemy.”

To accomplish this feat of daring, the pilot must take his plane and AO within a few feet of the ground to accurately identify the target as the enemy. There can never be a mistake, for friendly Vietnamese could suffer from the slightest error in judgement or plotting.

A young, bearded Marine sergeant during Operation Harvest Moon, late last month, commented on the AO/pilot teams who joke constantly on the hazards involved in finding and marking enemy targets. “How can you describe a complete nut as insane when they risk their lives in that plane no bigger than a butterfly to save our lives by finding the Viet Cong and calling in artillery.”

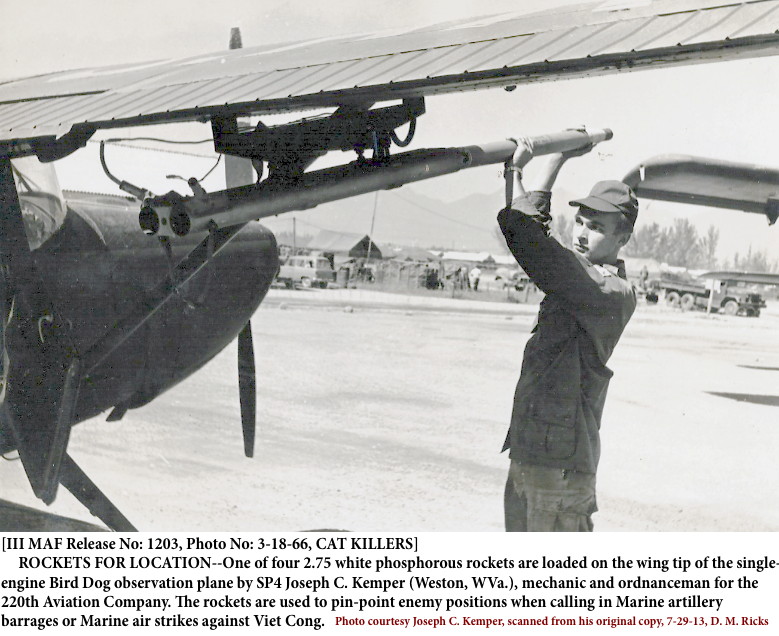

Calling artillery to support a Marine operation, or during a coordinated mission with U.S. Marine and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces is not unusual. Neither is calling for Naval gun– fire—or for that matter—Marine air strikes.

A firing mission or air strike can be on its way within three minutes of the time it is received at the Fire Support Control Center (FSCC) at Division headquarters.

Aircraft from the 220th, cold on the ground, can be launched within 10 minutes with a pilot/AO airborne, heading for the target area. And in many cases be calling for supporting arms before the wheels leave the runway.

“We fly when it’s humanly possible,” remarked Army Captain Robert L. Chancellor (San Antonio, Texas), 3d Platoon Commander for the 220th Aviation Company, 12th Aviation Group. It isn’t unusual to look into the sky by day or night and find a small observation plane cruising around, or seemingly diving into a water–filled rice paddy seeking the enemy in his many hideouts and means of camouflage.

“We Observe, is our motto,” said Capt. Chancellor, adding, “We’ve never been grounded by Weather, and we don’t anticipate being grounded. So long as the Marines and ARVN need our eyes and voice, we’ll be airborne.

The Marine aerial observer in the plane’s back seat is the eyes of the coordinated team of experts. He can spot, call and assess any target with accuracy and assurance. An average month’s flight time for the nine Marine AO teams is 597 hours, with from 2 to 10 missions during a 24 hour period.

Pilots average 90 flight hours each month taking the Marine aloft to scout for the enemy. The pilots are also trained aerial observers should the Marine become wounded and unable to continue his mission.

Each of the eight planes with the 220th has been shot by the enemy once, at least. Every pilot and AO has been wounded at least once, with the exception of one, Marine Captain Walter L Strain, senior 3d Marine Division aerial observer.

Capt. Strain, with more than 85 missions in four months of flying in Vietnam, offers no explanations for his fortune. The closely–knit team of marine and army officers, however, have some comments, like: “He lives a charmed life,” or, “He goes to church regularly.” In unison however they all agree the captain is “just lucky—for a Marine.”

The friendly rivalry between the Marines and Army exists even in this closely–knit team, as it does anywhere in the world. But their ribbing is limited to the ground not in the air.

There are normally two missions daily by the Bird Dogs, a nickname given the aircraft. But for Operation Harvest Moon, the largest coordinated American Marine and ARVN operation in Vietnam to date, as many as five aircraft were airborne at one time, with 20 missions in a single day.

The tiny specks in the sky were also responsible for directing flare ships over the Marble Mountain Air Facility when the Viet Cong sent suicide attacks at the field on Oct. 28. Their greatest effort to date, however, was Operation Harvest Moon, with five aircraft in the air at one time.

Though the Cat Killers fly like flying circus acrobats, and perform such feats as looking for men at night with their landing lights along a river bed, of “hand–delivering” messages to commanders in the field, there as been but one plane lost. That one was to a devastating Viet Cong fire. The pilot and AO survived, and will soon be flying again. There’s been no loss of life.

[Comment by SP5 Harry Kee: “Don’t know where they got that; we have already lost a couple.”]

Editor’s Note: Warrant Officer Ronald “Ron” Miller Fero, pilot, and Private First Class Marvin Leroy “Cowboy” Shipman, Crew Chief, were lost on 20 December 1965, 1st Platoon—Quang Ngai