Catkiller

By Norman S. MacPhee

Transcribed and edited for publication by Dennis D. Currie

Prologue

During the 20th Century, American citizens, when called upon, voluntarily went off to war for their country. Our “citizen” army has served the United States of America well during this period of U.S. history. There are as many stories as there are those who have served. I was standing alone in Arlington National Cemetery, looking at the almost endless lines of tombstones marking the resting place of those who have served, when I decided to write this story. It is a novel based upon events that occurred in the Viet Nam era. This story is dedicated to those ordinary citizens who served America when called.

CHAPTER 1

THE LETTER

I think everyone remembers where they were when they got “the letter” . This one came in the middle of the swing shift, in the dark, on a Minuteman missile site under construction near Minot, North Dakota. The site Superintendent (Super) brought the mail and says, “Hey, oiler, you’ve got some mail.” I responded that I’d read it after the shift. He replied, “Not this one”, and threw me the envelope. I opened it and it began, “Your friends and neighbors have selected you....” Damn, drafted!

Everyone knows it might happen if you’re not going to college, but, jeez, not to me! Since it had been forwarded, the deadline date was only a week ahead. Says I’m supposed to report to the induction center in Fargo for a physical. Wow, here we go! “Hey, super, I guess I’ve got to ‘drag up.’ I’ll finish the shift then you can call the union hall in the morning for a replacement.” Super says, “Okay, I’ll have your checks ready at the office in Minot by 10 am tomorrow. Sorry to see you go—you’ve been part of a good team here.” Yeah, sure, fun and good pay too. Well, I wonder what’s next. Super mentioned, “...it would be worth a try to see the recruiters in Minot in the morning when you’re there picking up your checks. They might have some ideas regarding the options available to you, like selecting Army, Marines or whatever...” God, Marines, no interest there, but, it’s worth a stop at the recruiting center.

The next morning, with my final pay in my pocket, I went over to the recruiting center and began with the Army sergeant. Thank God the Marine recruiter was visiting some small town for the day. The sergeant, whom I later learned was a staff sergeant, was friendly and very helpful, the last one I’d see like that for a while! He explained what getting drafted meant; an infantry enlistment, but only for two years, while the good programs required various lengths of service beyond two years. He suggested going down to Fargo for the physical and battery of tests to see what I was qualified for. He pointed out that the best program the Army had for an enlistee without a college degree was a new pilot training program where graduates became Warrant Officers. Boy, mom and dad were right about that college stuff—lots of better deals available if you were a graduate. Oh, well, too late now.

I stopped by my small home town on the way to Fargo. Not many of my friends were still at home. Most were either in college or at their jobs in larger communities. A few were farming. One last look around the gymnasium where all the basketball games we thought were so important took place. I did stop in to pick up a copy of my high–school credentials for the Army testing center in Fargo. My folks had since moved to the east coast, so there were fewer remaining ties to this small town. I did stop in to see a classmate that ran one of the local grocery stores and told him of my woes. He had already been through the Fargo center, but he was rejected because of a football knee injury—4F. I also stopped in to say hi to my grandpa and grandma before leaving for duty. I called my girl friend, Floy Ann, who was attending University of North Dakota in Grand Forks (the Fighting Sioux; since then it has changed to no–name!). She didn’t seem surprised that I was drafted after trying to get me to attend the university with her. We decided that I’d stop by the university before leaving North Dakota so we could say our good–byes.

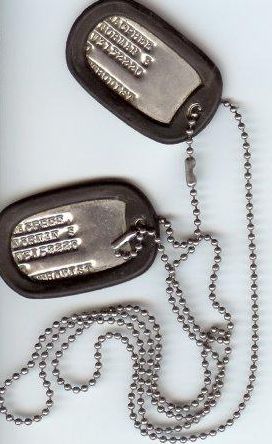

The Fargo induction center was just a taste of what was to come. There were long lines, lack of personal attention and very few friendly faces. I tried to give them my name once, Norm MacPhee, but the soldier taking papers said “here’s your number, we only care about your number, not your name." The physical did not take long. Later, I heard it described as “if you can see lightning, hear thunder and they look up your backside and don’t see daylight, you’re in”! Three hours of written tests followed, with the staff there telling us to come back tomorrow morning for the results. The next morning I found out that I could qualify for the Army Flight Program if I could pass a flight physical. They weren’t optimistic, and told me that seven had been sent to Minot Air Force Base for the physical and none had passed. Here we go, back to Minot again. Since my time for draft induction was approaching, the officer in charge of the induction unit extended my date for 30 days so that I could be tested.

Air Force medical personnel at the base in Minot were much easier to deal with than the Army folks down in Fargo—is there a message here? After lots of prodding and poking, eye dilation and other tests, they told me I passed, but it would be a few days before the information would reach Fargo. They suggested I find someone to drive me home, if I could, because the eye dilation medicine would not wear off for several hours. I had no one, so waited until it got dark to head down to my home town. My grandparents would be happy to see me again, so I had a place to stay until time came to go. Bird hunting season was open, so I took my grandfather and a shotgun and went to a few of the favorite spots he had taught me about. We took home two pheasants and a limit of mallards. It took us about an hour to pick and clean the birds. Grandma decided to cook the pheasants for supper. I also was able to spend a couple of days camping and fishing on the Missouri River, just below the dam near home, where there are lots of walleyes, and northern pike to catch. I grew up enjoying the out–of–doors and wondered if this would help me in the military world I was about to enter. The grain harvest season was coming to a close in central North Dakota. There were still a few “amber waves of grain”, but most of the wheat and barley fields were already in the grain bins.

I spent the few days I had left at home thinking about growing up in rural America. You knew everyone in your home town and many in the nearby communities. The rolling prairies were places where I had walked for miles hunting jackrabbits or sharp–tail grouse. There were farms where I had “picked rock” for the farmer to clean the ever appearing rock from his fields. The paper route that I worked all through grade school let me know every house in town. It also let me have the funds to purchase the first “English bike” in town—three speeds—wow!

I walked around the downtown area by the Drug Store, with its soda fountain and the Ford Garage that my family had operated until my father decided to return to Law School. There was the newspaper office and a bank, as well as three grocery stores and two hardware stores. Three service stations and a theater were located on “main street.” We were fortunate to have a doctor and dentist located in town. There were, of course, three bars and a hotel with a café inside. There was a second café out next to the highway, too. The pool hall and bowling alley had recently closed. Some changes were coming to the town. I stopped by the Auto Body Shop and said hello to two good friends of my father. The town cop stopped and invited me for coffee, so I joined him at the drug store for a donut.

On Sunday, I accompanied my grandparents to the small methodist church that had been so important in our lives in this small town. Sunday school, and, later, youth fellowship classes taught important life lessons. I also walked by the Veterans of Foreign Wars monument and, for the first time, noticed that there were names inscribed on the monument from both World War II and Korea. I recognized many of the family names of those who did not come home alive. For the first time in my life, I felt vulnerable.

A week later I contacted the induction folks, and a captain there told me to be in Fargo in ten days for the bus trip to Missouri. I’d be taking basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, a place I’d never heard of. Another week of saying goodbyes at home was followed by a quick trip to Grand Forks to say goodbye to Floy Ann. She was very busy taking classes so we had only the hour here and there and evenings. Floy Ann was a Minot girl, and I had met her here at the university while I had misspent a semester. I was never sure what she saw in me, since I was working construction and she was working on her degree in social work. The good bye’s finally ended and I was on the bus to Missouri. They told us to bring only two changes of clothes in a gym bag; so, none of us had much with us. We were sworn in as soldiers, and I was required to make an on–the–spot decision as to whether I wanted to go into training in fixed–wing or rotary–wing aircraft. I took fixed–wing.

CHAPTER 2

BASIC

There were already three busses ahead of us at the brightly lit reception center at Ft. Leonard Wood. We unloaded from the bus with our meager bags of possessions and were met by hollering sergeants wearing park ranger–type hats. They didn’t like anything about us, our haircuts, our clothing, our looks—anything. They called us ‘cruits, which later translated into recruits. After twenty minutes of getting us to line up for them, a speech ensued commanding us to turn in any “weapons” we carried. Gosh, I thought, why would anyone carry a weapon? I was then shocked when the sergeants provided a box for all to throw their weapons away, and over twenty knives and one pistol appeared! Boy, where had I been! It turns out that many of the guys at this induction were from St. Louis, where packing a switchblade or the like is normal. The confiscation being behind us, we were “back on the busses.” This happens a lot in the Army. Another trip to barracks where we were able to sleep for six hours or so.

Our first morning in the Army was busy and, of course, miserable. There were more hollering sergeants and line after line to stand in. Pick up your uniforms. No chance to try them on. The supply folks just guessed. They let you pick your shoe and hat size, nothing else. The Army sure liked green and brown, only the boots were another color—black. The haircut, if you could call it that, was quick if nothing else. My hair was short, or so I thought, but now I knew short! Then we put on the new army clothes and sent our civvies home. Another physical and shots came next. Then, the worst came, our introduction to our drill sergeant. He explained, in no uncertain terms, that he was going to be our mother and father and anyone else we had known in our past. He requested that we not confuse him with God. Rather, he stated, God worked for him too! He marched us. I later found out that this first attempt was not really marching, just stumbling to our home for the next six weeks.

We were all packing two army duffle bags full of our gear by this time. What a rag–tag bunch. I was assigned to 1st squad, 3rd platoon, Bravo Company, Second Battalion, Second Basic Training Regiment. The last three of these were to be known as B22 for short. It took weeks for us to find out just what platoons, companies and the like were all about. The sergeant had us label our duffle bags with markers and had us stand in our first formation. He asked if anyone had had prior service or ROTC. This was before we learned to be wary of volunteering. I raised my hand, since I had a misspent semester at our university, and he handed me (and others) black bands to put on our sleeves to make us acting corporals and sergeants for training purposes. I became a squad leader. I can remember wondering what this would mean. We found out the next day that we would be excused from KP (kitchen police) duty so that we could take turns at CQ (charge of quarters) duty. Also, we learned that we were blamed for anything that went wrong in our squad (or platoon for the temporary sergeants).

A couple of days later we had our names sewn on our fatigues as we began to learn the simple tasks of becoming a soldier. Lots of physical training took place every morning, including the Army “daily dozen,” followed by running in formation. Marching training occupied a lot of the day, as well as familiarization with the army system of rank and weapon familiarization training. We were each issued an M–14 (no ammunition) and these rifles were locked up in the barracks each evening, then unlocked and re–issued in the morning. Army food was okay, and there was lots of it although we were not given much time to eat during the morning and lunch meals.

Our barracks were old wooden buildings left over from, I think, WWII. They were heated by coal and we needed to have a man stand “fire watch” all night. This duty endured for two hours for each man, after which he would wake his replacement.

If you got sick, you could go on “sick call”, but, all I ever saw anyone receive for medicine was a bottle of “APC’s” or aspirin. You also got double duty when you returned, so not many went on sick call unless you were damn near dead. We were also encouraged to go to church on Sunday, and they gave you an hour to do so. We were paid in cash, at that time $78 per month. Then, some sergeants stood in line to get donations from you for charities. I remember ending up with about $65. ALL of this was spent on needed supplies such as toothpaste, soap and shaving materials. I could see that being in basic training was not going to be a huge economic event.

We learned about using gas masks, the Geneva Convention, standing orders, how to stand guard duty, run obstacle courses and march, march, march. The third week we began to march seven miles to the rifle range with our packs and all. This was after an introduction to the M–14 and how to disassemble and reassemble the weapon. Our first day on the rifle range was spent sighting in our individual weapons. The march home to the barracks was the last time we saw our Platoon Sergeant. He just quit showing up. We found out two weeks later that his wife, using a frying pan, had put him in the hospital. How could this happen to such a nice guy? We knew where the schedule was posted for each day, so we just showed up there or marched to the required location. No one seemed to know or care whether we had a Sergeant.

There was a fellow in my squad named Long who had volunteered for the draft to get away from home. The Army was not the social event he expected, so he was trying to get out by not doing anything. He wouldn’t even shower or make his bed. The rest of the squad did it for him for a while, but one night while I was serving on CQ duty, they beat the heck out of him. Man—blood everywhere! He still wouldn’t do anything, not even shave. I went to our Recruit Platoon Sergeant with the problem and suggested that he go to the First Sergeant and explain the situation to him. “ Not me, ” says he. I was afraid for Long’s health. He was only seventeen and apparently a Mama’s boy of some kind. I finally got up the guts to go knock on the First Sergeant’s door (we had been trained how to report if required to do so). I was told to enter and shakily stood in front of his desk and said something to the effect, “Private MacPhee requests permission to speak to the First Sergeant.” He looked up at me, chewing on his cigar and said, “What the –––k do you want”. Even more shakily, I related the problem with Long. The First Sergeant then says, “Why the –––k don’t you go to your Platoon Sergeant?” I related that we hadn’t seen him for about ten days. His mouth dropped open, and from a room behind him an Officer appeared. They both questioned me at some length about both Long and the Sergeant and asked how we had been getting to training. I related that we just followed the posted instructions. The Sergeant then said that he’d take care of Long and that I was to “...get the –––k out of his office!” I could see that we were not going to be great friends.

The next morning we had a new Platoon Sergeant, and this guy was black. We were even more scared of him than the first one. He was with us to the end of training, and it was better to have a real sergeant around. As for Long, the First Sergeant came and got him about 4:30 in the morning and had him in Army issued civilian clothing at our morning formation at 6:30. Long was made to shave dry three times before he was pointed toward the bus stop with a ticket home. He had been given a “Section 8” discharge as “unable to adjust.” After watching this, no one else in the company tried that. A couple of recruits went AWOL (absent without leave) for a night and were introduced to the MP’s (military police) and the stockade.

We went on a field trip with full gear. This meant camping out in the red mud at Ft. Leonard Wood. I didn’t even know dirt could be red. It was black where I came from. They introduced us to the infiltration course, which means crawling under lots of wire, at night, in the mud, while they shoot machine guns over your head and set off explosive charges all along the crawl route. Then we made more trips to the firing ranges. We mostly shot at pop–up targets from 25 meters to 400 meters away. I was very surprised at how accurate you could be with the peep–sighted M–14 out to 400 meters. From the prone position, you could hit the man–shaped target every time.

Finally we finished basic training and graduateed. Everyone received individual written orders. We were going on to AIT (advanced individual training), such as combat engineers, some to artillery and some to armor. There were special schools, too. Some went on to be mechanics, equipment drivers, telegraphy, and clerical school. We sat around that last evening talking about how much we had learned about the Army without really knowing it. The next day, after a big parade, our sergeant and an officer actually called me by my name for the first time—Private MacPhee. Better than ‘cruit or –––t-head, like most of the time. Most of us were given up to two weeks between basic training and our next school. I went home to North Dakota for a few days. I was able to say hi to the grandparents and Floy Ann before heading to Ft. Rucker, Alabama. I got there via train to the Washington, DC, area, where I was able to spend a couple of days with Mom and Dad. I then boarded a bus to Alabama. This school should be a lot more fun than basic training. Little did I know....

CHAPTER 3

FLIGHT SCHOOL

There was a military transport available from the bus station in Dothan, Alabama, to Ft. Rucker, so I took it to my new post. I wore my class A uniform on the bus because it gave you a much lower fare if you traveled in uniform. Two duffle bags held all my clothes—most, by now, military.

The bus dropped me off close to the brick barracks of the fixed-wing flight program. I carried my bags into the main office at the barracks and was surprised to find it nearly abandoned. My orders were presented to the soldier on duty. He looked at them and said to me, “You’re a day late. That class, 64-3F/W, began

yesterday. Boy, are you in trouble.”

I looked at my orders, and I was here on the right day. Apparently the orders were wrong. Maybe they would forgive me. The soldier (I later found out that students here are called Candidate) made a phone call, and in about ten minutes a first lieutenant showed up and read my orders. He said, “Well, you’re late, but I guess it’s because your orders had a typo or something. Follow me.” He led me down the hall to a room with two bunks in use, and one empty. He gave me ten minutes to stow my gear then showed up with a Sergeant Tyson in tow. The next two hours were the worst of my life.

LT Pierce and SGT Tyson took turns hollering instructions in my ear and face and making me “drop” to do push–ups at each mistake I made. There were lots. I did learn, after about an hour, that I was to address them as, “sir, candidate MacPhee, yes sir” or “Sergeant, candidate MacPhee, no sergeant”. I later found out that I missed a whole day of this “monkey drill” by showing up a “day late”. Each of them asked me every ten minutes if I wanted to quit yet. They stated, over and over, that their job was to make me quit. One had to stand against the wall in their presence with both heels and shoulders hard against the wall. I also learned that candidates were not allowed to wear shoes in the barracks, must salute drinking fountains before taking a drink (and requesting permission from the fountain first) and must stop and present arms (salute) every Dempsey Dumpster you passed, whether alone or in formation. Each of my mistakes earned demerits. At the end of the two hours, they explained, I had enough demerits to restrict me to barracks for three months. I didn’t yet know that none of us would leave their sight for those three months. I was so sore in the shoulders from doing push–ups that the next morning I had to shave by moving my face. My arms wouldn’t move!

I found out that I was known as a pre–flight candidate and that all candidates above me in rank rated a salute. I also learned that we were promoted to E–5 for pay purposes only. There were junior, intermediate, senior and super–senior candidates as they progressed through the program. Rank differentiated each class by colored tabs worn on the epaulets of your uniform. I learned, from classmates that evening that there were 138 candidates in 64–3 and that four had already been thrown out or had quit. Wow, all this before I even showed up. The rest of the class was really tired as they had been run, harassed and otherwise victimized all day beginning at 4:30 am. All of us were hard at work trying to shine shoes, shine brass, arrange uniforms as per the picture instructions handed us upon arrival and clean the barracks—and I MEAN CLEAN. The floors of tile were already polished to a mirror shine, and the bathrooms and showers were spotless. I met my new room–mates; one, like me, came directly into the flight program from basic training. Aother had applied was a former first sergeant. We were all being treated the same. About half of our classmates were those who had been sergeants or specialists before applying for the flight program. These “prior service” guys had a real advantage over those of us who just finished basic training. They pretty much knew what was expected as to uniforms, bed making, uniform display and shoe care. The new guys learned a lot from these “old soldiers”. I don’t think many of us would have made it without their advice and help.

The next morning, my first full day as a candidate in 64–3 began at 4:30. We first completed the Army “daily dozen” exercises, then, went on to run six miles. Many of my classmates “fell out” temporarily to empty their stomachs, then caught us to continue the run. These early morning exercise periods were followed by a thirty minute period to shower, dress and clean the barracks for inspection. We then fell out for about fifteen minutes of pure harassment before going to the chow line for breakfast. We did lots of push–ups and spent some time in the “dying cockroach” position, which is best described as being on your back with arms and legs in the air. While standing in the entrance line for chow, we were required to do pull–ups and sit–ups before being allowed into the mess hall. Here, we were expected to eat “square meals”. This consisted of sitting on the front four inches of your chair at attention with your hands in your lap. When you decided to take a bite, you picked up your fork (or spoon), then, for the first time you were allowed to look down at your food. You then picked up the food with your utensil after which you were required to again look straight ahead, then bringing your food to your mouth with square movements and replacing your fork on the table before chewing your food. All during this process the officers and sergeants were pacing up and down looking for mistakes. Any transgressions of the square meal procedure were punished by having the candidate get up and stand on his chair yelling out “I’m a —ing dummy”. Boy, anyone who was overweight sure lost it fast as we were not able to eat much that first week.

Following breakfast we formed up and were marched to “pre–flight” classes. These classes taught us about military affairs unrelated to flying. This process, if you lasted, was to continue for six weeks before any flight training was to take place. Afternoons were spent on obstacle courses, gas training, confidence courses and physical testing. Every afternoon, before evening meals, we were performing parade practice. We were given thirty minutes per day to run to the Post Exchange (PX) area where we got haircuts, turned in and picked up laundry and picked up supplies. You soon learned to share these duties with classmates as there just wasn’t enough time to accomplish all your duties by yourself. We learned to keep our uniforms in perfect condition. Our displays of clean clothes were also without flaw. Our shoes and uniform brass were shined brightly, and even so, we all received enough demerits to last our entire military enlistment. The pressure was more than any of us had experienced. The constant lack of sleep combined with the personal harassment by cadre and upperclassmen caused quite a few to “SIE” or complete a “Self–Initiated Elimination” form. Others students were eliminated by the cadre. Their method of eliminating someone from the program was to come and get them at night. In the morning, they were just gone! I lost a room–mate through elimination and never even woke up!

After six weeks of this, you get pretty good at doing what is expected of you. The cadre called us out into formation on Saturday morning of our last week in pre–flight and told us that we had been a “pretty good class” and that we were going to get the weekend off. We cheered as one. The air went out of us as they then announced, “ Now, here is what you are going to do on your ‘weekend off’”! We were all depressed, but we never let them get to us again after that.

We had been required to assist the cadre in eliminating our own classmates by completing a paper we called the “—k your buddy system”. You rated each of your classmates from top to bottom. The cadre then tabulated the results and eliminated the bottom two. This took place every two weeks and it was really difficult for each of us to do. I had always been pretty good with numbers so I suggested to our class leader that he let me fill out all of the sheets next time. I merely started with a class list on the first page, then, the top individual was inserted on the bottom of the next page and so on. Everyone ended up with the same compiled score. When that happened, the cadre, nice guys that they are, made us run two six mile runs the next morning, then, we were required to re-complete the forms. We did it the same way and all of us again received the same score. They left us alone on the “—k your buddy system” after that! Those six mile runs became a little easier to take once you got used to it. There was a rule that an officer had to run with us, so, we just picked up the pace until the officer puked. They then followed us with three officers in a car and they would take turns. You can get even for some things.

When pre–flight ended we were down to 66 in the class after starting with 138. The cadre had kept their word for over half of those beginning the course. The pressure reduced after we started flight classes. This was not so much that the cadre lightened up, but, rather, we were in class half of each day and at flight training the other half so they only had us evenings and week–ends. The flight classes were very interesting and the Army instructors were all very good at their specialty. They broke the academic training down into navigation, weather, flight theory, aircraft maintenance and instrument training. The flight training was divided into primary, “B” phase, instrument or “C” phase and tactics. In primary you learned to fly the O–1 (also called the L–19 and “Bird Dog”). This training paralleled what you would learn in civil training for a private and commercial license. In “B” phase we learned to land the aircraft in very short and difficult landing strips and on roads, in fields and on steep hills. You became very confident in your skill to operate this aircraft in difficult landing areas. You also became very good at using the radios and navigating under “visual flight rules” or VFR.

“C” phase was very professional training to fly aircraft under instrument conditions meaning “in the clouds” without visual reference to the earth. We used a second aircraft for this—the De Havilland Beaver or U–6 in army terms. We flew with two other students (the aircraft accommodated six) and the three of you became known as a “stick”. After the first couple of weeks in this phase we began to fly under actual instrument conditions, and we would make three short cross–country flights each day under instrument flight rules or IFR.

The time just raced by during the flight portion of our training. We were very busy and didn’t even notice the progression through status from “junior” candidate through “intermediate” and then “senior”. As Christmas was about a month away we learned that the Flight School would shut down for 2 weeks for the holidays and that we could take leave if we wished. I had been exchanging letters every week with Floy Ann, who, at this time had graduated from the University and was working as a Social Worker. I called and asked if she wanted to get married over Christmas, and she said yes. I really missed her a lot and could now see our way clear to make a living as a military pilot. We were married during the Christmas holiday and both returned to Ft. Rucker for the final month of training. I was also a “super–senior” at this time and we were no longer harassed. We also trained in tactics at this time, learning to fire rockets, adjust artillery, drop supplies, pick up messages without landing and live in the field. One of the classes was a three–day “escape and evasion” problem where you were left in the swamps without supplies and told to try to get to an airfield. We were all captured at went through a simulated prisoner camp. They were allowed to “torture” us somewhat, by putting us in boxes too small to hold us, making us sit in our shorts in a chigger pile where they bit the heck out of you. I got partially even when left in the interrogation tent for a few moments alone. I urinated in the coffee thermos used by the interrogating officer.

Graduation day arrived. What a great day. 54 of the beginning 138 of us made it. You are transformed from being lower than a snake to being an officer, or nearly an officer. A Warrant Officer is allowed to attend either the Officers Club or the NCO (noncommissioned officers) club. Each class member received orders for their next assignment. This was a really exciting time. Some went to Europe, some to Korea and a couple to a place we could not find on the day–room globe, the “Republic of Viet–Nam”. My orders were to Navy Lakehurst, New Jersey as a pilot attached to the Electronic Support Command at Ft. Monmouth, NJ. The reason for Navy Lakehurst was that Monmouth did not have an airfield. Floy Ann and I packed up the car (our stuff at this time would fit in her Mercury Comet) and headed north. We stopped for a couple of days in Virginia to visit my folks, then on to Tom’s River, NJ to find an apartment.

CHAPTER 4

FIRST ASSIGNMENT

First Assignment! We found an apartment in Tom’s River on the third floor of a beautiful old home. We lived among the squirrels. It was a good thing that we didn’t have much stuff as it was three steep flights up. Floy Ann was really enjoying “fixing up” the place to suit her needs. I drove out to Navy Lakehurst and up to the gate. Marines guard the gate at navy bases. After having me register my car, they let me in and pointed to Hangar 5 where the army was located. This is the blimp hangar outside of which the Hindenburg crashed and burned. I walked in to flight operations with orders in hand and was sent to the CO’s (Commanding Officer’s) office. The CO was a Lt. Colonel and seemed like a nice guy. He welcomed me and told me to make my self at home and look around. I would be working for Captain Kanouse and would also have an additional duty as Assistant Maintenance Officer working under Major Balint in that capacity. The colonel related that Maj. Balint was away at a school, so I should stop by and introduce myself to SFC Winslow, the maintenance sergeant. I saluted before leaving and headed off to operations again where I met my new boss, Captain Kanouse.

Kanouse informed me that our main mission was to support Ft. Monmouth and that we would fly aerial photo students in O–1’s and several aerial platforms used in research of airborne electronic devices. We would also be transporting people from Ft. Monmouth when requested. We had 54 aircraft in our detachment, including helicopters. Some of the work was classified, so now I knew why all the pilots received secret clearances before we left Ft. Rucker. Captain Kanouse said he would put me on the flying schedule for tomorrow at 9 am, so I was free until then. I decided to stop by maintenance and meet Sergeant Winslow. He was doing paperwork when I showed up, and I told him of my conversation with the colonel. He welcomed me aboard. I related that I had no idea whatsoever what an assistant maintenance officer was supposed to do so maybe he would enlighten me if the need arose. He laughed at that and said that he would let me know if any help was needed and that I should stop by during times I wasn’t flying and he would show me the ropes. Great!

As I turned to leave, he said, “Oh, sir, there is one thing. The marine guards at the gate are supposed to perform random searches of vehicles, but they don’t. They only search army enlisted men, and they search us all, every time. I said “OK, I will look into it”. I had no further duties for the day so I headed back into town. As I came up to the gate, I saw a small building nearby that was labeled “USMC Office of the Guard”, so I stopped by there to inquire about the gate problem. There was a marine first lieutenant at a desk labeled “Officer of the Guard.” He was the only person around since it was nearly lunch time. I saluted him (he didn’t return the courtesy), and asked if I could speak to him about the gate guard system since I was new on base. He said, “Sure”, but make it quick.” I did and related to him that the random searches his men were supposed to do included searching all army enlisted men each time they passed through the gate inbound. He immediately replied that “I should mind my own —king business”. I asked if I could use a phone. He said I could. There was a base phone book there and I dialed the office of the base commander. I found out that he was an admiral when his secretary answered the phone. I asked to speak to the commander and the secretary wanted to know why. I briefly told her and she put me through. The admiral asked what he could do for me and I related the problem with the non–random searches. I also told him that I was calling from the marine office at the gate. He asked that I put the marine officer on the line. I did so. This guy stood at attention while he was talking on the phone. Lots of “yes sirs” and “no sirs” then a final “yes sir,” and he hung up the phone. He threw me out of his office. I was forever famous with the detachment enlisted men as the one who had stopped the searches, but I paid a price. I was searched every time I entered for a year! Live and learn, but it was worth it this time.

The assignment at Navy Lakehurst was a prime one. We got to fly great assignments and I was trained to fly the old DC–3, my first twin engine aircraft. We had lots of time for training too. Many of our assignments took us cross–country including several trips to Texas and one to New Mexico. I also was assigned to fly a Beaver to Ft. Ord in California with only a maintenance man along. We were to be there for 3 weeks testing some electronic gear with Sylvania, then be replaced with another team. What a trip. Flying across the US at 105 knots lets you see the place.

Meanwhile Floy Ann had found a job with the local Social Service section of the county and was working. She was also enjoying learning the ropes of being an officer’s wife. We had to do some entertaining and both of us enjoyed that. We also made several trips into New York City and enjoyed the visits. Quite exciting for a couple from North Dakota!

Tom’s River was very near the beach, so we were able to spend some time out in the sand. We quickly learned that the beach was no place to be on the weekend since New York City seemed to empty out in our direction at the end of the work week. If we were able to get to the beach during the week it was great.

CHAPTER 5

THE ORDERS

The conflict in Viet Nam was now common knowledge in late 1965. We all knew that it was just a matter of time before pilots would be sent over to this one. My orders came after 10 months. . . . to go to a school to learn to fly the De Havilland U–1 “Otter”, then to Vietnam. We had Otter’s at Lakehurst, so I was able to get the orders changed to train at Lakehurst before I left.

I was to show up at Travis AFB in California in January for the trip over. There were lots of things to do before going. Floy Ann gave notice at the office and decided to spend the year with her folks in Minot, ND. She called the County welfare office there and they offered her a job for the year I’d be gone.

Anyone going to Viet Nam had to meet with the Army lawyers and prepare a will. Boy, that’s uplifting! One also had to take lots of shots from the medics. My shot record seemed to be full after plague, yellow fever, typhus, typhoid, smallpox, cholera, yellow fever, tetanus, flu and polio. The plague shot made me sick for a couple of days.

I got checked out in the Otter and flew on the regular duty roster until 30 days before my Travis departure date. . . . we then took leave to move Floy Ann to North Dakota and, after some tough good–byes, I boarded the Frontier Air Lines flight that would take me to Minneapolis, then San Francisco.

CHAPTER 6

OFF TO WAR

Upon arrival at Travis I checked in at the BOQ for departing Viet Nam bound officers. In two days I’d be on my way. I didn’t travel with anyone that I knew, but, in the service it doesn’t take long to make friends. Two nights in the Officer’s club and I met several others that were headed to Saigon too.

The morning of departure an Air Force bus showed up to take us to the flight line. All of us going on this flight were either pilots or Army Special Forces soldiers. We were to fly on a C–141 cargo plane. This was a new Air Force aircraft at that time. The cargo hold was split into three sections; a small section at the front of the aircraft where a container housed toilet and feeding facilities, a seating section in the center facing to the rear and, finally a cargo section at the rear of the aircraft. We all noted that the Air Force loadmaster had a lot of fun with this load. The cargo we were facing consisted entirely of empty coffins!

The trip over took 5 days because of weather and the fact that the C–141 was in the initial phase of being used by the Air Force and could not be fully fueled yet. We stopped at Hawaii, Midway, Wake, Guam and Manila. We were allowed off the aircraft for re–fueling and for over–night stops, but, were never allowed to go far. Everyone, I think, was afraid to be going to war. We have trained for this, and I had great faith in the aviation training we had received, but this was really going into the unknown. No one spoke of fear, but everyone had it, I’m sure. . . . I sure did. There was also the issue of being able to shoot someone if you had to. This we did talk about. Anyone who had been in combat would share that it would not be a problem when the time came, but we all wondered. The next on our agenda was Saigon.

CHAPTER 7

ARRIVAL

When the aircraft landed at Saigon and they opened the tail section for us to get off, we were hit by the heat, humidity and smell! It was about 120 degrees on the asphalt. As we headed to a place next to the airport labeled “Replacement Depot” with our two duffle bags over our shoulders, I heard a familiar voice yell, “Hey, MacPhee,” and I saw one of my flight school classmates nicknamed ‘duck.’ He motioned me to come over to his aircraft, a cargo carrying army Caribou. I picked up my two duffels and did so. He laughed when he showed me their load. They had just landed from an outlying airport and the entire load consisted of body bags with dead Vietnamese soldiers contained therein. That was the smell.

We signed in to the “Repl Depot,” as the replacement depot was called, and gave a set of our orders to the staff there. We were assigned a cot in temporary tent quarters and told that we would have two days to process into Viet Nam. We were allowed to go downtown Saigon in the afternoon. I went once. It was so hot and humid that nothing was enjoyable.

Everything on the airfield was military. There were lots of aircraft, jeeps and 2 ½ ton trucks hauling men, equipment and supplies. There were lots of Vietnamese too, both military and civilian. We had not been issued weapons or ammunition yet, and didn’t understand anything about what was going on relative to how to tell who the good guys were. We could hear and feel artillery pounding in the distance at night. This was to become a familiar sound.

The Vietnamese people were very small. Most were a foot shorter than the average American and they weighed about 80–90 pounds. The men that were not in the military (at least in Saigon) wore slacks and shirts much like we did, but the women wore a dress of silk like material over a blouse and loose pants. The streets were filled with people and vehicles. There was a bicycle driven rickshaw known as a cycelo. (sick–a–lo). They had the seats for riders in the front and the pedaling was done from behind.

God, was it hot and humid. I thought Alabama was hot!

Much of the city of Saigon was built by the French while they were in Viet Nam, so many of the streets had French names. Many of the residences had masonry fences around the lot with guards at the gate. I got to know a couple of other pilots who arrived when I did and we jointly hired a cab and went downtown to have a meal at a hotel. This was really the only time we had to ourselves as we spent the rest of the time processing. One of the processing items was to turn in all American money in return for “Military Payment Certificates”, known as MPC’s or “funny money”. We also purchased some Vietnamese piasters for use on the local economy. Fortunately, 100 piasters equaled $1, so, a piaster was a penny.

The morning of the third day several of us, all pilots, were to report to Nha Trang, about half way up the coast toward the DMZ (De–militarized Zone). We made the trip in an Air Force C–130 cargo aircraft. There were fold–down seats along the wall of the aircraft; most of the load was cargo, but there was plenty of room for us.

Nha Trang was a lot like Saigon, only smaller. We were picked up at the airfield and taken to temporary quarters and told to appear at a building nearby at 0800 next morning. The next day was our assignment day. Each of us, 3 Warrant Officers and a Lieutenant, had orders to fly Otters, but the Colonel in charge of the 14th Aviation Battalion told us he needed O–1 (Bird Dog) pilots in Da Nang. . . . and promised that if we served 6 months in Da Nang he would see to it that we flew Otters the last 6 months. What choice did we have? We were issued new orders for Da Nang as well as weapons and ammunition. The rifle was an M–16 and I took 10 clips of 20 rounds each. I had qualified on the M–14, so I had to get some help on assembly. We were also issued a .45 automatic pistol with shoulder harness and 2 clips. The other pilots at the local BOQ had some fun with us telling us that no one had ever returned alive from as far north as Da Nang. Pilot humor is not always the best! We also heard that Da Nang is in I Corps, (there were 4 corps in South Vietnam) and that I Corps was operated by the Marines. We were going to be assigned in their support. How is it that I always get to work with these guys?

There was a small officer’s club at the airfield at Nha Trang, and I met a couple of pilots that I knew from flight school. They were flying Otters, which, they related, was a good job. Neither of them had been shot at in their 6 months or so. The Army pilots in Nha Trang lived in a “villa” which turned out to be a large home surrounded by a wall topped with concertina coiled military wire and with the gates guarded by a South Vietnamese military man. My friends could not enlighten me about duty in I Corps to the north, so we just enjoyed a drink together.

The next morning, all four of us, Lt. Brinkley, WO De Los Santos, WO Medley and I boarded an Air Force C–123 for the trip to Hue, Phu Bai in I Corps. The aircraft kept getting noisier and smaller as we proceeded north to our new home. This did not build confidence regarding our assigned location. Our arrival in Phu Bai was greeted by a sign over the only building at the airfield, “220th Aviation Co. Home of the Catkillers.”

CHAPTER 8

CATKILLER

We immediately reported in to the building with the sign and met the CO of the 220th. We quickly learned that we were to be assigned to Da Nang, and that the 220th Aviation Company had three platoons, one at Hue, Phu Bai, covering the northern portion of I Corps, one at Quang Ngai, covering the southern portion of I Corps and Da Nang covering the largest and central portion of the Corps. We spent only one night at Phu Bai and boarded yet another aircraft, an Otter, for the hour or so trip to Da Nang.

The Otter landed at Da Nang Main airfield and taxied us right up to the operations shack of the 220th. There we met our new Platoon Leader, Captain Chancellor. He shared with us that we would be living at a small “villa” at 9 Gia Long in downtown Da Nang and would eat at the Officers Club a short walk away. The platoon had 2 jeeps and one ¾ ton truck assigned and the officers used the jeeps and the enlisted men, who performed the aircraft maintenance and fueling, used the ¾ ton. We loaded our gear into a jeep and were driven to our new home at 9 Gia Long. I roomed with Lt. Brinkley, and the other two Warrant Officers roomed together.

We were introduced to our “hooch maids” or Vietnamese women who would wash our clothes, iron them, clean our rooms and polish our boots every day. They accomplished all this for 300 piasters per month, or about 3$ US. The name of our hooch maid was Ba Hoa. The Ba means “married lady” and Hoa was her last name. An unmarried woman was addressed as “Co” instead of “Ba” and a man was “Ong”. I never learned what Ba Hoa’s first name was. We had hot water for showers 3 days per week and power most of the time. Our room had a ceiling fan and, after one got used to the heat, it was adequate for sleeping if the power was on. Once a week, in the evening, there was a Vietnamese interpreter available for us to communicate with our “hooch maids”. His name was Lon Hung, and he was a student at the University in Hue. His English was very good and it was interesting to talk with him about Viet Nam since he was the only Vietnamese that we knew to speak the language well. Lon taught us a lot about the country and shared that most of the people were uneducated peasants and were considered the “bending reed” when it came to politics. This meant that they followed whoever was in control and just bent with the wind that was blowing.

Our first day at the flight line was spent taking a very short O–1 check flight with Captain Chancellor, and issuance of maps and assignment of visual reconnaissance areas. We also learned that we were to fly at 800’ above ground level (AGL) for recon purposes, and, then, if we were receiving fire, climb to 1,500’ AGL. We spent the rest of the day laminating our maps, so they would last, and meeting the other members of the Platoon as well as the enlisted men including their boss, the Platoon Sergeant. We also learned that our call sign would be “Catkiller” followed by the last three digits of the aircraft tail number. Army pilots are not assigned the same aircraft all the time, rather, assignments are random. Call signs, in this manner, were not the same for a pilot every day. This was the Army way!

We also inspected the aircraft we would be flying The O–1 in Viet Nam was much like the training model. There were a few differences, these had 4 rockets each, and 3 radios, 2 FM (Frequency Modulated) for talking to ground personnel and one, UHF (Ultra–high Frequency) for talking to other aircraft and aviation related stations such as airport towers. There was also a “flak jacket” folded on each seat. Hopefully this would protect your most important parts from small arms fire! We wore one of these flak jackets too. They were some protection against small arms fire and shrapnel caused by a bullet passing through the aircraft. The radio switch panel allowed you to listen to all three radios at once although a transmit switch limited you to talking on only one at a time. There was a transmit button on the power handle and a second one for talking on the intercom only to your observer. This model also had a variable pitch propeller, which was supposed to make the aircraft faster, but heavier. There was a survival kit behind the rear seat and the fuel tanks were lined with some type of “goop” that was supposed to make them self sealing in the event of small arms hits. I wondered right away about getting hit in the fuel tank with a hot tracer round. This is not something to dwell on!

We were also introduced to the other pilots already assigned there. They were Capt. Teer, Capt. Hartman, Capt. Murray, Lt. Johnson and Lt. Morris. WO Medley, WO De Los Santos and I were the first Warrant Officers assigned to the 220th. The initial thinking was that only “combat arms” officers should be assigned to the company. This meant you had to be infantry, artillery or armor trained. Some of the officers that were there when we arrived let us know that they didn’t think that we were qualified for the job. That all stopped when I suggested that if there was any particular mission for which they didn’t believe me qualified that they would be welcome to replace me on that mission. This was mostly just “new guy” harassment, but, a little goes a long ways.

CHAPTER 9

MISSIONS

The 220th platoon at Da Nang had several major missions to perform. The first, and easiest, was the “north coast recon” and “south coast recon” each day at first light and again just before last light. We flew the coast of I Corps north to the DMZ and south to the edge of II Corps. We carried a Navy Officer in the back seat during these missions. We were supporting the South Vietnamese “Junk Fleet” which was supposed to keep the North Vietnamese from using the sea as a method to re–supply forces and to prevent any movement of naval or river craft by the North Vietnamese or Viet Cong. These missions were usually quiet and very effective. One time I saw a boat (smaller than a ship anyway) out to sea north of Da Nang, and I radioed the junk fleet to check it out. As they approached they began taking fire, so the navy observer in the back seat called for artillery support (we were close to shore). The boat was quickly sunk. There were several “Junk Fleet” outposts at the mouths of rivers along the route. These were small, heavily defended outposts manned by South Vietnamese and one American naval advisor. We would drop mail to these lonely guys every time we would get any. The coastal reconnaissance was important, but not very active, since the folks involved were completing the mission of not allowing incursion from North Viet Nam, by boat or ship.

A second mission was to fly recon missions back into the jungle areas of central I Corps. The topography of the whole Corps area consisted of a narrow (2–40 miles wide) coastal plain where most of the population lives, and the mountainous jungle area (20–100 miles wide) covered by triple–canopy jungle. I was assigned two such areas and tried to fly them each once each week. This mission required “two ships” since we would be flying back so far from assistance and radio contact that one ship would “fly high” and do nothing but watch the low working aircraft in case something went wrong and the aircraft crashed. If that would happen, one would never find it by visual means as the canopy would hide any sign of the aircraft on the ground. My “two ship” areas contained two Special Forces camps where 4–6 American Army SF men and 80–200 South Vietnamese and or Nung troops would man the camp. Nungs were paid mercenaries reportedly migrating in from China long ago. They were reputed to be good and reliable fighters and their families were in the camp with them. These “two ship” mission areas were mostly for prevention purposes. We were looking for any roads, trails or other sign that the enemy was using the area. The Special Forces camps were at Thoung Duc and Tien Phuc. There were also two more camps close to my area. A Shau and Kham Duc.

A third mission was convoy cover. When a military convoy was to travel from Da Nang (usually north toward Hue), they asked that a Catkiller accompany them during the trip to provide artillery spotting and air support if needed. This route north out of Da Nang went over Hai Van pass which was a narrow winding route through the nearby mountains. It was a favorite place for the enemy to place mines and blow up bridges to prevent passage. During the French war in Indochina, this highway, highway 1, was known as “The Street Without Joy” for obvious reasons. The air cover mission worked mainly as prevention. Whatever works!

The fourth mission, taking most of our time, was to fly my primary recon area on a daily basis. I was assigned to “Quang Nam Special Sector” which was close to and south and west of Da Nang. There were lots of US Marines operating in this sector, and they had a major artillery base at hill 55 south of Da Nang. There were also units of the South Vietnamese Army as well as South Vietnamese Regional Forces and Popular Forces (known as RF’s “RUFFS” and PF’s “PUFFS”) I would fly this area every day, sometimes two missions, with, usually, a US Marine Corps Observer. These observers were very professional. They were trained as Forward Observers (FO’s) and as Aerial Observers (AO’s). They had already served six months as FO with a ground unit and, so, they understood the ground unit issues in detail. We received fire every day by enemy with their small arms on these missions. Fortunately, they were not very good shots, and, when we began receiving fire we climbed to 1500’ above the ground instead of our standard 800’ visual recon altitude. Our aircraft would be hit from time to time, and our maintenance men patched up the holes and painted a small “busted cherry” on the side of the plane for each hole. One of our aircraft had 16 of these painted on the door!

A fifth mission, which wasn’t used very much, was the leaflet drop as part of the “Psywar” (Psychological Warfare) effort. We dropped leaflets that, in Vietnamese, told the enemy how to give up. We dropped some that indicated that, if they shot at our aircraft, our aircraft would kill them. There were many different types including “free passes” to give up and become a South Vietnamese loyal. There were also small gift packets containing a small amount of tobacco, salt and a South Vietnamese flag. We didn’t even know what some of these propaganda leaflets said, we just dropped them when and where we were told.

At the end of each mission we would complete a Visual Reconnaissance (VR) report. These reports would all go to the office of G–2 air. This is the air intelligence office at the General staff level. They would compile all the reports and add them to other types of intelligence reports and it was amazing how they could track enemy movement, unit designations and the like. We received periodic briefings from the intelligence officer assigned to air and this was helpful for us too. One depressing part of his brief was to discuss the issue of being shot down or going down for other reasons. He’d point out that the average life of a downed pilot was 15 minutes and that this included some who made it for weeks! It doesn’t take much of this information to make your tummy tighten when you strap in to your aircraft.

CHAPTER 10

VIETNAM AND THE VIETNAMESE

Vietnam was a whole new set of sights, sounds and smells for and American soldier. The market places, where much of the food was purchased by the local people, was filled with strange garden items and fruits as well as very smelly fish and even smellier “nouc mam”, which, we learned, was the favorite fish sauce to spice up the staple, rice.

The rice paddies, whether from the ground or the air, were new to us all. Since the weather in the country was always good for growing rice, there were these small fields surrounded by dikes everywhere and in all stages of growth from just planted to those just harvested. The Vietnamese had ingenious methods for lifting water into these fields. One such method consisted of a basket with two ropes attached on each side. This was operated by two people in a swinging motion which dipped water from a lower source and elevated it into the rice paddy. There were all sorts of water wheels powered either by people or water buffalo. These water buffalo were slightly larger than a steer in the U. S. and they were seen singly as well as in large herds. We found that they were used as farm animals for pulling plows in the rice paddies and other chores. I think that every American soldier had a photo of a small Vietnamese boy with his water buffalo. The boys charged 1 piaster for the picture.

The coastal plain was covered with rice paddies and small villages. The villages contained small huts covered with thatching and grass bundles. These huts had a floor that was up off the ground and the occupants slept on mats directly on the floor. They seldom had any chairs. The Vietnamese rested by squatting on their haunches. The huts contained very little. Most cooking was accomplished with charcoal as a heat source and only a couple of cooking pots were available along with the simple tools of a rice farmer.

Back away from the coastal plain was the jungle. This heavy growth consisted of three levels of canopy. The huge teak trees towered above the other levels of undergrowth and small trees. Vietnam was a very green place. The heat and humidity were constantly with you. There were also new “critters” to deal with. Lots of cockroaches and small lizards called geckos. These small, transparent green guys were, at first, disconcerting to see crawling across the ceiling above your head in bed. You then learned that they ate mosquitoes, so they became welcome occupants in your room.

We did not have a lot of contact with the Vietnamese people. This was due to several factors. First, we were very busy and had only one day off per week to go to the PX to get supplies and take care of personal business such as mailing packages. Second, the Marine General in charge of I Corps, General Walt, placed the city of Da Nang “off limits” to American military personnel. And third, it wasn’t always safe to wander around the city, especially unarmed.

One of our contacts was with our “hooch maids”. They spoke no English, and our Vietnamese was nonexistent! There were a few words in French that would work since the French had been in Da Nang so long. We did not see these folks very often anyway, since they were accomplishing their work while we were out on missions. They really did a good job cleaning our clothes, shining boots and keeping our rooms clean. All for about $3 per month for each American. These maids were from the peasant class of people and wore black silk billowy pants and white blouses with a conical “rice hat”. All were dressed the same.

We had an elderly Vietnamese man, “Papasan”, who was in charge of hiring and supervising the maids, and he cleaned up our operations shack and helped our platoon leader with various duties.

We had several Vietnamese Officers that flew with us as observers. They knew the country well and were excellent artillery observers. We always took them when we were supporting a Vietnamese ground operation. They were all bilingual to some extent, so, they were of great help in dealing with language problems. One such officer, a captain, was a favorite of the pilots. He was always happy and a real professional. I ended up with an extra refrigerator and no one in the unit wanted it, so I gave it to this captain. He was speechless! He later invited one of the other pilots and me over to his place for supper. His small two–room home had no plumbing and a dirt floor with a single hanging bare light bulb in each room. There, in the main room, plugged into a socket above the hanging light, was the refrigerator. He showed us where seven of his neighbors were keeping their things separately within the refrigerator and freezer. They had developed a system so that all could use it. That evening he served us steaks barely warmed in a wok. They knew we liked steaks, but didn’t know how to cook them! We ate sitting on the floor. The family of four was very nice, and the rice and vegetables were great. The steak was a little raw, but we ate it anyway. The neighbors all stopped by to “say hello” while the captain introduced them and translated for all of us. We showed them pictures of our wives, and they asked lots of questions about America. This was a big night in the life of this Vietnamese family, we could tell.

CHAPTER 11

AIR STRIKES AND INCIDENTS

Many of our missions became “routine”. While on four out of five missions we were shot at, much of the fire was from a single soldier and such fire was ineffective. If we could locate the source of the fire, we could use artillery or air strikes to hit back. It was not worth it to do so for a single individual. We also had our four 2.5 inch rockets which had high explosive (HE) warheads, but they were best used for marking targets for strike aircraft. These rockets were not very accurate, and our “sights” for firing them consisted of a vertical metal rod mounted just behind the propeller with a band of tape on it. This was lined up with a colored grease pencil mark on the inside of the aircraft window. Each pilot had his own grease pencil color. Mmine was yellow, an appropriate color under some conditions! A normal mission lasted three ½ hours, not including pre or post briefing or reports. The fuel in the O–1 would last 4 ½ hours at the most.

Many incidents began with a radio call on the FM (Frequency Modulated) receiver that would go “any Catkiller, any Catkiller this is 4–1 alpha, over”. We would respond immediately since these were usually Marine units needing assistance. We would first ask them to key their mike for 10 seconds since we could then home in on their signal. After we turned toward them, we would ask what the nature of the assistance they required. They were usually under enemy fire and requesting artillery or air–strike support. Once we located them, we could tell if they were within artillery range and always preferred to use this method because of great accuracy and ready availability. . . . The enemy, whether Viet Cong or NVA (North Vietnamese Army), of course knew where all the artillery was, so, they would usually wait until an American unit was outside of range before attacking. If the troop unit was outside of the artillery circle, then we would use strike aircraft. To request an air strike we called “Landshark” . . . . these were the controllers for aircraft going to North Vietnam and those in I Corps. I never knew the location of “Landshark”, but they sure did a good job of sending us help when we had Marines or other soldiers in trouble. They had a powerful transmitter and, you could hear them all over I Corps. These folks would divert you a flight immediately, but the problem with the first flight (of four aircraft) was that they had whatever ordinance they were to use on their primary target before being diverted. If they were headed to a bridge near Hanoi, they carried, usually, 500 pound bombs. . . . Not the best ordinance to use near friendly troops since the blast area was very large. After the first flight, Landshark would send you flights with ordinance made to order. I always asked for napalm and 20mm cannons since the first was very effective and the last was very accurate.

When an airstrike was imminent, lots was happening at the same time. You first had to determine where every friendly in the area to be hit was located. The strike aircraft would contact you on a pre–assigned UHF (ultra–high frequency) channel previously assigned by Landshark. The strike aircraft would contact you as soon as they were inbound and you would give them an approximate location from Da Nang, such as 240 degrees at 50 miles. They would give you their call–sign, usually, in our case, Oxwood or Condor followed by their flight number and a “dash 1”. A flight may be called Oxwood 64–1, meaning the 64th flight of the day, with the “dash 1” meaning the flight leader with his three other flight members as “dash 2” and so forth. As soon as the inbound flight contacted you they would report their ordinance and time to “bingo fuel” or time they MUST leave the area to head home. I learned that this “bingo fuel” meant enough to make it home and to make two approaches. Not much spare fuel! These strike aircraft, when inbound, also needed to have target information such as; target elevation, wind direction and estimated speed, nearest friendly troops and direction and distance, direction of requested roll–in strike heading and direction to break off the target. (Example here is roll in heading 020 degrees, break right upon leaving the target) These strike aircraft were so fast that they seldom saw the target as we did. That’s why they needed us to locate and direct them as to where to drop or fire their weapons. Most of the strike aircraft were either F–4 Phantoms or A–4 Skyhawks. . . . the A–4’s were the best, from our point of view, since they were slower and more accurate for our purposes. The pilots of the strike aircraft also wanted to drop napalm first since they did not relish many passes over a target with large canisters of gasoline hanging from their wings! I don’t blame them.

About once every ten days or two weeks each of us would have a significant incident of one sort or another. The three described below are examples of such “out of the ordinary” missions.

One such incident began with the typical “any Catkiller” plea for assistance. The unit that contacted us was located outside the Marine artillery circle, so while headed their direction I called Landshark and requested air support for an American ground unit. Even before we reached the unit needing assistance, an Oxwood flight checked in with a ten minute arrival time. We arrived over the unit, and there we saw two Marine helicopters (the old H–34’s) in an LZ (landing zone) picking up two Marines who had been wounded by mortar fire. We immediately noted that the H–34’s were taking automatic weapon fire from the south and, so I went to the “Guard” or emergency UHF frequency monitored by all aircraft, and transmitted “Marine choppers south west of Da Nang—clear the zone, you’re taking fire from the south” . Since the wounded had been loaded, they immediately departed. The ground unit radio operator quickly briefed us that the fire they were receiving had stopped upon our arrival (it usually did), and that they were going to let us locate the bad guys. They had not received any direct fire, only mortars, so did not know the direction of the enemy.

Both my observer and I had seen the fire from the south aimed at the choppers, so we decided he would adjust Vietnamese artillery fire at that location. Using Vietnamese artillery was difficult since one had to process through an American at the artillery location who was bilingual. While he was doing that, I briefed the Oxwood flight which was now circling above. We decided to use them to hit a hillside to the north. Although we had not seen any enemy there (or anywhere else yet), it looked like a likely place. I also called Landshark and asked that they not send any more strike aircraft until called. We used napalm and 20 mm cannon all over that hillside and assured ourselves that no “bad guys” remained there. The marine captain in the rear seat had adjusted artillery on the southern location and no fire was coming from there either. The ground unit commander relayed that they had received no new fire.

The strike aircraft had expended their ordinance and departed, so we were the only air asset in the area. We decided to remain and look for any sign of enemy. After another hour flying at 1,500 feet, we had seen nothing. It was our policy, once we knew that enemy were nearby, to remain at that altitude or make a very low pass to see if we could see anything. We decided to do so, and I selected an east to west route that would take us directly over our friendly unit. We explained to them our intentions. Just after crossing the unit we had to “pop up” over a tree line, and as we were descending again I caught movement out of the corner of my eye to the left. Looking that way, I saw a long trench line filled with enemy soldiers. These guys all had grass and branches in their head gear and had looked, from above, like a line of small trees or rice paddy dike with grass on it. We immediately climbed to our 1,500 foot altitude again, and now that we knew where they were the enemy troops were easy to see. After informing the ground unit as to the enemy location, we were going to call in air strikes again.

Just as we were about to call, we noted a huge formation of army helicopters flying up the coast, south to north, about fifteen miles away. I called them on “Guard”. “Army choppers south of Da Nang, contact Catkiller on 222.2 (an easy to remember frequency we used on UHF).” The Army Huey’s immediately called back, and we asked if they had gun ships available. They affirmed that they did and that they had about an hour of fuel, so we asked for their assistance. A short time later, they were on location pounding the enemy with 2.5 inch rockets and M–60 machine guns. The helicopters, in this war, were very good strike aircraft since they were slow enough to see the target once you pointed it out. The Marine unit did not take any more casualties and, after the strike was over, counted over three hundred enemy casualties. All were North Vietnamese regular soldiers in uniform and well armed and supplied. We were very low on fuel by this time, so we headed back to Da Nang. While enroute, we called our unit and asked that another O–1 be sent out to help these Marines until dark.

Two weeks later, when the Marine unit commander was sent back to town for a rest, he brought our unit two cases of beer from his unit—the ultimate compliment!

Another “any Catkiller” call came from12 miles south west of Da Nang just as we lifted off for our afternoon recon mission. This Marine unit was in the process of performing a sweep north through a large village where there were reported to be lots of enemy. Upon arrival, we could see that the village was bordered on the west by a small river and that the Marines had three tanks on the west side of the watercourse. . . . no one would escape that direction! The Marine unit was already in contact with the enemy in the village and was about to land a “blocking force” to the north and east of the battle area to prevent escape in that last direction available. They gave me the location of the impending air arrival by two Marine CH–46 helicopters, and I immediately asked them to move the landing location 300 meters north–east where the helicopters could land behind a hill and would have terrain cover from the village being attacked.

The battle commander, south of us at an artillery base at “Hill 55” over–rode my request and ordered that the original LZ be used. Here came the choppers. As they began to slow for landing (full of troops), an enemy automatic weapon opened up on the lead chopper and must have hit a fuel tank, because the aircraft just exploded. The second helicopter was committed to land too, and was taking the same fire. The pilot came on the radio and said that he had lost an engine and was going down. Marines were jumping out of the helicopter at 200 feet, willing to take their chances. . . . the chopper pancaked in to a rice paddy and two Marines got off and then the chopper took off again with that one engine and no load. We were speechless. We had just witnessed the sudden loss of about 40 Marines and an H–46! The two Marines that survived from the last chopper did perform a blocking force function that allowed the unit sweeping up from the south to kill over 350 enemy. At what cost though! Just after the helicopter fiasco, a very strong transmitter came on the air and told the battle commander that he was relieved of command and to report to Marine HQ in Da Nang. It turned out that this entire action was being watched and listened to by the Commanding Marine General from a hill–top command center west of Da Nang. He did not like what he saw. This day was not a good one for the enemy, but not for us either. War is like that.

Another incident began when I was the “duty pilot”, meaning, I was just waiting in the Operations shack for a call to go. I heard someone yell and I looked out to see one of our Marine observers, a Captain, running across the PSP (pierced steel planking) aircraft parking apron. . . . he was wearing his flak jacket, so I grabbed mine and met him at the ready aircraft. We both jumped in and began to buckle our harnesses when he finally caught his breath and could talk. He said our mission was to shoot down a U.S. Air Force O–1 just like ours, only gray. What is this???? Well, says he, those four F–4 Phantoms you see circling overhead have been launched to shoot the plane down, but they can’t locate him. This aircraft has been repeatedly shooting rockets at Marines west of Da Nang. Wow! This one wasn’t in the book! We contacted the overhead aircraft and made sure they knew that we were a friendly O–1 going out to locate the unfriendly one. I could look up and see that they carried the lethal air to air missiles.

My observer contacted the ground unit that was having the problem and we flew over to his location. The ground commander stated that the aircraft had left about 10 minutes ago after having been there 5 times, firing 4 rockets each time. We stayed in the area for about 30 minutes, never seeing another O–1. The F–4’s flying overhead left temporarily to perform an aerial refuel. I suggested that we wouldn’t need four aircraft for this one and the flight leader agreed and sent two home. After more consultation with the ground commander, we left the area intending to fly back to our base since we could not locate the other aircraft. Less than 3 minutes later, the Marine unit called us and said “he’s back, he’s back, and firing again”. We turned around and, sure enough, there was an O–1 in Air Force gray about 4 miles ahead. We watched him fire a rocket as we were inbound, and I tried to contact him on UHF emergency frequency. . . . no answer.

We had a slight advantage over the Air Force bird. We had a variable pitch propeller, and his was fixed pitch. This gave us about a 15 knot advantage. He was obviously in a square rocket–firing pattern. We caught up and could see that the aircraft held an American in the back seat and a Vietnamese in the front. We caught the attention of the American and pointed back to Da Nang. . . . The American spoke to his Vietnamese Pilot and then turned to us and shook his head, no. My Marine observer then took my M–16 and pointed it out the window at the other bird dog and pointed back to Da Nang. . . . The other aircraft immediately turned back toward the main airfield “Da Nang Main”. We followed him back and, approaching the field, contacted the tower to relay that we were following an Air Force 0–1 in and not to let this, or any other 0–1 take off until release by us. The tower operator asked under what authority we made this demand. I suggested that he look up and see the F–4’s above who were about to shoot down any aircraft we pointed out!

We followed this O–1 into the landing pattern and taxied behind him to his ramp space. There were several Birddogs there with Air Force and Vietnamese pilots. We jumped out of our aircraft and confronted these guys asking why they were firing rockets at Marines! Silence! What the hell is going on here? One of the Air Force pilots was a Lt. Col. He finally was able to share with us that they were teaching the Vietnamese to fire rockets and were unaware of the Marines on the ground! Sometimes you wonder if we are all on the same side. We all went home with a story to tell! No one was hurt this time.

Upon arrival back at our airfield, the orders promoting me to CW2 (Chief Warrant Officer) arrived. This promotion was automatic after 18 months unless you had performed some horrible act. The pay increase would be nice.

CHAPTER 12

The Power and the Politics

There came a time during this assignment that each of us became amazed at the power that had been delegated to us as recon pilots. With just a flick of a microphone switch, the entire power of the U.S. military was at your service. This position is unique in the service. We were not given this authority because we were promoted within the command structure, but, rather it accrued because of the mission assigned to us. We did not need to “radio back” to headquarters for authority to fire artillery or direct air strikes. We were on our own.