OUR FLIMSY AIRCRAFT:

by Gene Wilson, Catkiller Historian

With all due respect for the great introduction of Jim Hooper’s, A HUNDRED FEET OVER HELL—on the inside flap of his book cover—were our Birddogs flimsy (a characterization which Jim has attributed to his publisher, Zenith Press, as hyperbole rather than a ‘non–aviator’ understatement), or simply thin-skinned, both physically and in other characteristics as well?

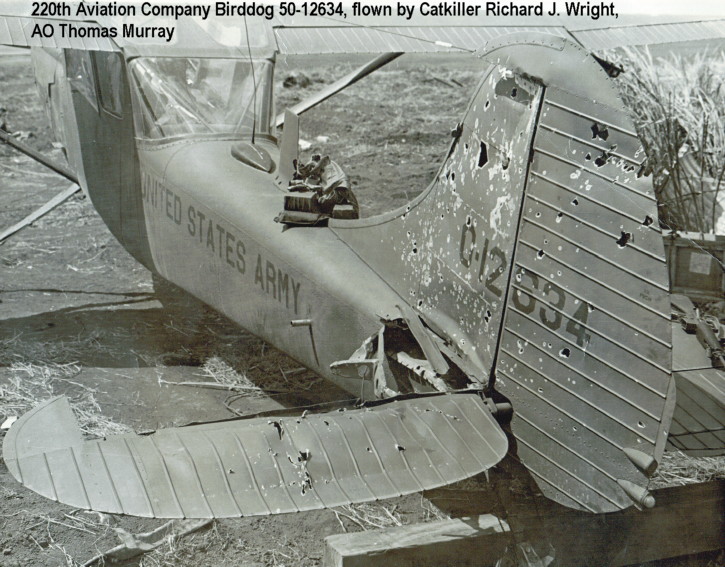

Except for the Chicken Plate that was wired under the seat in some aircraft, or the armored seat which was later added to pilot’s throne area, there certainly was not much armored protection against all that was thrown against our thin–skinned O–1’s. While its thin skin may have been pretty flimsy, as many bullet hole patches would attest, I believe that we can also reflect upon the fact that the airframe of our warbird was pretty fairly sturdy and substantial. Just the forces of some of our evasive maneuvers might tell us that both the pilot and observer trusted, and tested frequently, the many factors of glue that held them and their aircraft together on a few more missions that we might not care to remember in detail.

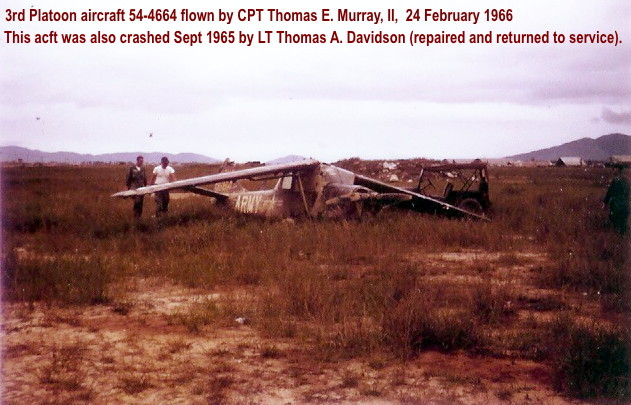

The photos below are examples of things that went wrong, but the crew survived when the airframe, or what was left of it, eventually landed under the circumstances. We also know that many of our Catkiller aviators, who were or became more than just simply pilots and/or airplane drivers, with the Grace of God and a bit of guts ball at times, nursed some pretty sick birds and crew members, themselves included, home on several occasions.

Well, you'll get the picture, as these photographs speak more than a thousand words:

COMMENTS:

Regarding the last three photos depicted above:

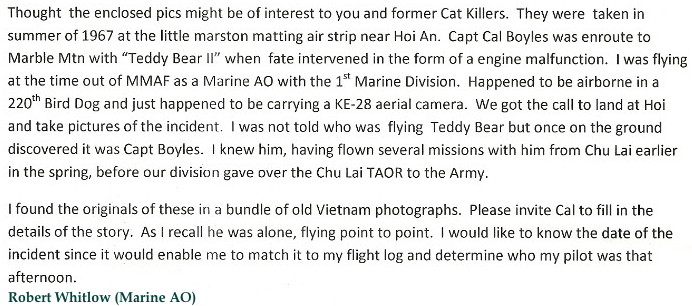

Don, et al,

I do not recall the tail number.

At that time, I was the maintenance officer for the 1st platoon. That aircraft had just been assigned to 1st platoon after coming out of a complete “ZeroTime” overhaul. Over the first week or so of flights, we had three warning lights indicating metal in the oil. Each time, we performed the designated procedures for draining, flushing, installing a new magnetic drain plug, and refilling the oil. I reported this problem to Company headquarters, and was directed d to fly the aircraft to Marble Mountain for an engine change.

I am terrible at recalling names, but I was accompanied by a Warrant Officer who was a standards pilot. A few miles from Hoi An, the engine started losing power and the cockpit began to fill with smoke. The Chief guided me through some procedures to try and keep the bird in the air, but to no avail - we were forced to land as soon as possible. Our first choice was a beach landing, but as we turned in that direction, we noted that there was a large firefight at that location, so we elected to try to get to Hoi Anh. When we approached the strip from the South, we had a strong tail wind, and agreed I should try to make a landing from the North. It became apparent that we we were running out of airspeed, altitude, and any good ideas, so I turned to try a mid field touchdown. We almost made it - with the left landing gear on the strip, but the right gear caught the embankment, flipping the aircraft straight down the runway, but bouncing the bird and veering to the left edge of the strip. breaking the fuselage.

I shut off all the switches, opened the door, grabbed my weapon and ammo and got out of the aircraft. As I was doing this, I heard the Chief yelling for me to get out. I looked back—he was not in the aircraft. He had climbed out the window head first, dropping his pocket knife out of his pocket, reaching for it, putting it back in his pocket and then completing his exit—and running about 10 meters down the strip!

When I walked over to him he was yelling at me, “Damn good landing!, Damn good landing!” I said that I didn’t think so—I had broken the bird. He asked me if I was hurt, and I replied nothing more than the web of my throttle hand being a little sore. His reply was, “I’m not hurt either—Damn good landing!" Later, we found out that the area around the strip was mined, and if we hadn’t made it to the runway, we would have been in dire straits.

Shortly after this event, the Chief was reassigned to Battalion headquarters as the Standards Officer, and received the Review Board report on the crash. The initial report found me responsible, BUT he discovered that they had intermingled parts of two separate reports. He straightened that up, and the revised report did not find me to be at fault.

Warmest regards to all.

Cal Boyles

Both Catkiller pilots (and their AOs, I presume) walked away from these events. Norm can fill in any details....

Gene Wilson

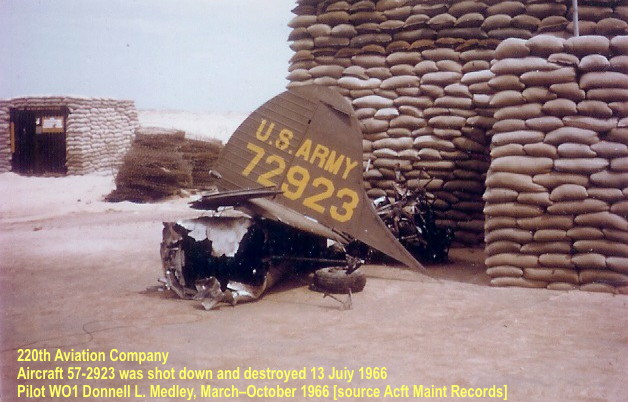

Comment by Norman MacPhee: Don Medley was not shot down by friendly fire, rather by enemy fire down near Hoi An. They ran to a Marine outpost, through a mine field, to escape and Don got the DFC. His aircraft is the pile of scrap.

The friendly fire incident was Don Johnson, flying a night mission over a Temple where the folks were holed up after an unsuccessful coup against Ky. His aircraft was force landed and they walked away.

The other picture here is one of Tom Murray’'s aircraft after it was hauled back to Da Nang Main while we were flying out of there. I never knew if he was shot down or ran out of fuel.

Norm

[Editor: No photo of the aircraft flown by CPT Don Johnson.]