EVERETT: Early Catkiller History, 1965—66:

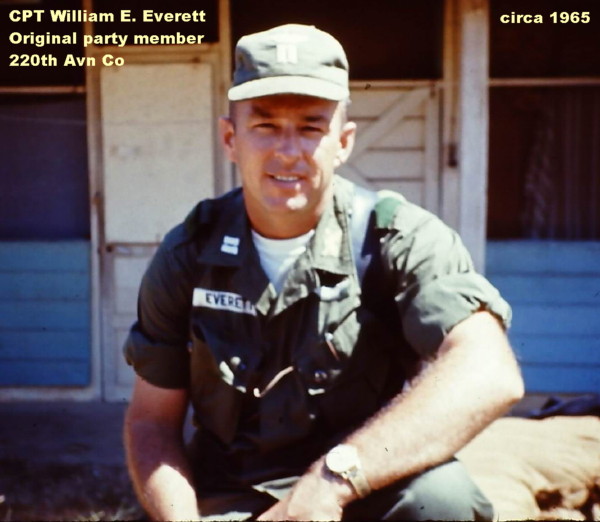

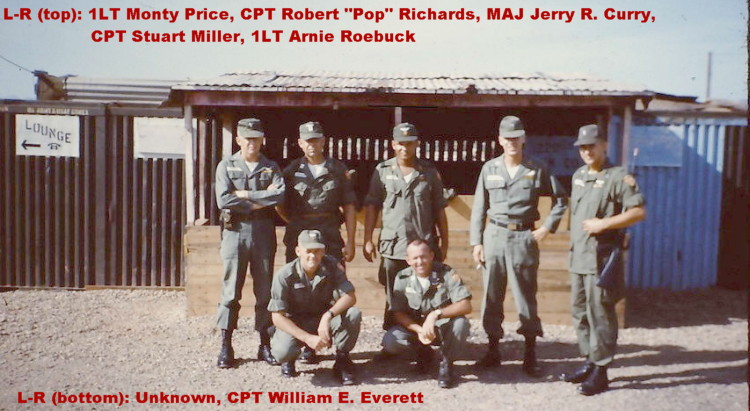

Editor’s Note: William E. "Bill" Everett, CPT, Catkiller 16, 1st Platoon Leader (MAJ Ret.), one of the original Catkillers (Cat Killers) wrote the document below:

After completing the advance course, I was assigned to Department of Maintenance, Fort Rucker, Alabama. After a three-week, "Methods of Instruction" course, I was assigned to the Aircraft Systems Branch teaching aviation mechanics. Later I was assigned as Chief of the Forms and Records Branch.

This lasted until about the 13th of April of 1965, then assignment orders came through to join the 220th Aviation Company, Fort Lewis, Washington. And I knew I was going to Viet Nam and War. After a 30-day leave, I said goodbye to Virginia, Susan, Bill, and Linda, and then flew out of Atlanta Airport to Seattle, Washington and Fort Lewis, Washington.

At this point I am going to enter excerpts from the Official History of the 220th:

UNIT HISTORY

220TH AVIATION COMPANY

15 APRIL 1965—31 DECEMBER 1965

THE 220TH Aviation Company (Surveillance Airplane Light) was organized at Fort Lewis, Washington on 15 April 1965 in accordance with the authority contained in DA Message 707331 dated 16 March 1965 and Sixth US Army General Order 28 dated 29 March 1965. Personnel fill date was programmed for 15 May 1965. No TO&E (TABLE of ORGANIZATION & EQUIPMENT) was published for the unit. Instead, paragraphs from three existing TO&Es (1-7D, 1-59D, and 55-500R) were utilized with some additions and deletions.

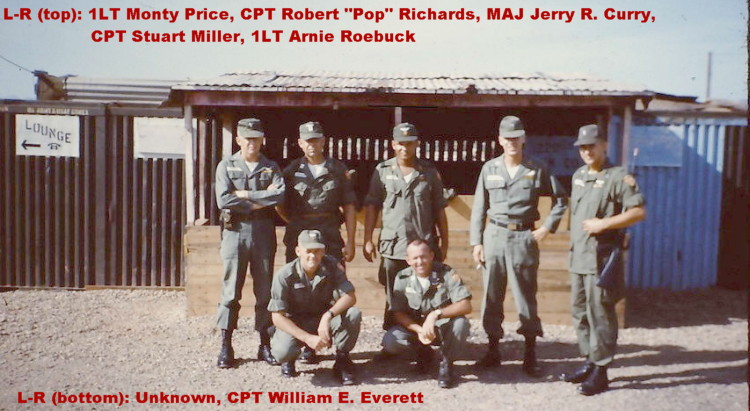

Organization and equipping of the company was accomplished under the able leadership of Major Jerry R. Curry, 094285 Infantry. Equipment less aircraft, was drawn, packed and delivered to the dock in Tacoma, Washington on 10 June 1965. At the same time the equipping was being accomplished the personnel were undergoing a vigorous POR qualification program to include rigorous physical training.

At the same time, and in an adjoining area at Fort Lewis, the 231st Signal Detachment (Avionics Repair) was organized and prepared for shipment with the 220th. This detachment was attached to the 220th for avionics and repair support and has remained with the company headquarters since. It was commanded by 2/Lt. Robert P. Covino, 05019174, Signal Corps.

The unit did not draw aircraft in CONUS but was programmed to pick them up in the Republic of Viet Nam upon arrival of the unit in country. With the exception of aircraft, the unit shipped approximately 99% of authorized equipment. The only items not drawn were cameras and related equipment, which had not yet been released by the manufacturers. (Note: they never arrived the year I was there.)

The main body, led by the executive officer, Captain William O. Schmale, 097970, Artillery, closed out at Fort Lewis and departed McChord AFB, Washington at noon on 1 July 1965. The company was transported in three C-130 transports direct to Da Nang, RVN. The first aircraft landed at Da Nang at 0230 hours on 4 July 1965; the third and final aircraft on 6 July 1965. The company was at 82% authorized enlisted personnel strength and 100% officer strength upon arrival in RVN.

Upon arrival at Hue-Phu Bai Airfield all hands, including officers, set to work building bunkers and installing a triple concertina fence around the barren sand pile that was to be the 220th home. The unit was given a target date of 1 August 1965 to be operational. The first operational surveillance mission was flown on 5 July 1965.

Now for my personal memory of this time:

After a short leave, I joined the 220th about 14 May 1965. As the fourth senior Captain in the company, I was assigned as the Platoon Leader of the 1st platoon.

At Fort Lewis, we stayed busy, bringing our medical shots up to date, firing for qualification on the weapon ranges, chemical training and of course the clothing and equipment checks. Concurrent with this we drew the company equipment, everything from kitchen pots and stoves to tool kits, and weapons. Everything but the trucks and jeeps were packed in 8’8’8’ steel containers for shipment to Viet Nam. Of course our destination was a big secret. But everyone knew the army was sending complete units only to Viet Nam. Of course we carried our weapons.

To keep the pilots busy other than with the above details, we were flown via Air Force C-123 aircraft to Wichita, Kansas to pick up L-19s to fly to San Diego, California. I made one trip and that one was fun. We had canvas bucket seats along each side of the aircraft facing toward the middle, no insulation and the noise was so loud we had to yell in a person’s ear. Plus, no heat or air-conditioning, but we did fly under 8,000 feet altitude so the ride was rough.

Going back to San Diego we left Wichita as a flight of four aircraft. Our first stop for fuel was Amarillo, Texas at an air force Bomber base, then on to Albuquerque, New Mexico to another air force base for fuel and to spend the night. Next morning we started engines and my starter shorted out with a cloud of smoke. Called the tower for the fire engine and got out in a hurry. We waited for a couple hours and found that it would be two days for a new starter, so I sent the rest of the flight on to San Diego, and two days later I also left late in the day for San Diego.

Flew on to Flagstaff, Arizona then up to Las Vegas, Nevada for the night. Taxied to the tie down area and saw a sign, "GAS HERE-FREE LIMO TO TOWN AND ROLL OF NICKELS" ($2.00), so I stopped, gassed up, and paid with my military credit card. Got my roll of nickels and took the Limo to the Thunder Bird Hotel. My room cost $12.00 (I was being paid $25.00 per diem for food and lodging.) Played two of my nickels in a slot machine and won $7.50 and bought a ticket for the dinner theatre. Had a good dinner and comedian JACK BENNY put on a two hour stage show. Also spent about $3.00 for two drinks and called it a night. Next morning flew in to San Diego Naval Air Station, turned over the aircraft, and caught a ride with the air force back to Fort Lewis, Washington.

After this one flight, my time was taken up getting the 1st platoon ready to ship to Viet Nam, with one major exception: A week or so before we shipped out, Virginia flew in from Atlanta and was there for a week with me. With other visiting wives and their husbands, we all stayed in a motel near the base, a very lovely week and a sad parting when she had to fly back home, knowing we were going in harm’s way.

Captain Quigley, our operations officer had spent a tour in Viet Nam. And his advice was to take as much lumber, nails, plywood and screen wire as we could beg borrow or steal. We did THAT and any other items we felt (from experience) we would need. Our approach was that the Army would furnish us with airplanes, weapons, ammunition; the rest was up to us.

We packed all of our company’ tools, equipment, building supplies and other items in CONEX containers that were 8’8’8’ in size. We were not told how many of these we could ship, so we loaded up with everything we thought we would need and shipped it.

What a company this was! The company commander Major Curry had commanded a Battalion; each of the four (4) platoon leaders (me included) had commanded companies. One or two other officers had commanded companies including a transportation officer who was in charge of shipping the company lock stock and barrel to Viet Nam. We had more talent in that company.

So, now back to the advance party, there were seven officers and nine enlisted men, Major Curry, the operations officer, maintenance warrant officer, and the four platoon leaders. Sergeant Sandoval was the senior enlisted man and our mess sergeant. He was the finder (scrounger) of items we needed but were not issued; this plus he was an excellent mess sergeant. The other men were supply and heavy lifters (workers).

Our trip to Viet Nam started in the morning at the Officers Club with a Champagne breakfast, and then we left Fort Lewis to board a train at Tacoma, Washington for Travis Air Force Base, California. It was an overnight trip, but we had sleeper cars and a club car. We were so keyed up that we spent most of the trip in the club car.

Arriving at Travis AFB, the next morning we checked in and were assigned to a flight the next morning. We were given rooms for the night, and we all sacked out. Late that afternoon, we (officers) went to the club for dinner and the partying started again. We were finally escorted out of the club at 02:30 by the Military Police and went to our rooms.

The next morning, the day we were to fly out, we overslept, and were awakened by Sgt. Sandoval, his men got us up and dressed (we were very much under the weather) packed our bags and put us on the bus to the terminal. He checked us in while the other eight men stood around to keep us in a group. When we boarded the aircraft each officer had an enlisted man as a minder to assist us on board, seated in the proper seat and safety belt on. Then they went to assigned seats. I went to sleep immediately and only woke up as we were landing in Hawaii.

This stopover was a two-hour refueling stop, and we were told to stay in the military terminal. I ate a brunch of fresh pineapple and papaya, the best I have ever eaten, then coffee and still more coffee.

At the end of the two-hour layover, we were informed that there would be another hour delay, and then another delay was announced. I suggested that we make reservations at Fort DeRussy, a military rest/vacation site on Waikiki beach, and we did.

The aircraft was repaired four days later. Four glorious days on the beach, with the rooms costing us $1.50 a night and mixed drinks in the club costing $.25 each. We partied for four more days. Life was good.

After two aborted attempts at taking off, we finally made it off the ground. Every pilot on board was in a cold sweat by the time we were off the ground. Because of the late takeoff from Hawaii, we could not make a night landing at Tan Son Nhat airport, in Saigon. So we diverted to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines.

We were assigned rooms off base in a Philippine motel, had a meal in the officers club (which was an old classic from the 1920’s) then took a bus to the motel, that judging from the number of women knocking on the door, was a hot sheet no tell motel. Early the next morning we ate breakfast at the club. Life was still good.

And we boarded the aircraft and a few hours later landed in Saigon.

So much for the good life!

After in-processing, we were assigned to tents next to the airfield, for our stay in Saigon. These tents came complete with cots, heat, no fans, and hordes of mosquitoes. The next morning we found a Bachelor Officers’ Quarters (BOQ) that had extra rooms, a bar, mess, and air conditioning, and moved in.

Now for the official histories take on the advance party and the next few days in Saigon:

An advance party of seven officers and nine enlisted men commanded by the unit commander, Major Curry, departed for RVN on 19 June 1965. They arrived in Saigon on 26 June 1965 and set about preparing for the main body’s arrival. Much staff co-ordination was necessary and the party split with each man working on a different problem. The advance party completed its work in the Saigon area on 30 June and with five airplanes, picked up in Saigon, proceeded to what was to be home for the 220th-Hue-Phu Bai Airfield, a small civilian airfield 14 kilometers southeast of the city of Hue.

This is what really happen in addition to the staff coordination:

We arrived at the beginning of the massive buildup of troops in Viet Nam, and you would not believe the confusion. Our friends who had been in country for a while gave us the "low down" on the supply situation and how screwed up it was. The people in Saigon (headquarters types) skimmed the cream of supplies. Everyone wore jungle boots and tropical fatigues, and affected the look of combat veterans. Of course the boots were clean and the fatigues were starched and pressed.

We were old experienced soldiers, and we knew the army would supply us with planes, ammunition, and food of some kind. The comforts of life we had to get on our own.

Captain Rogers (Platoon Leader 2nd Platoon), looked up an old friend, a Warrant Officer he few within Europe, and as luck would have it the Warrant Officer was in charge of reassembling army aircraft when they arrived in Viet Nam. Captain Rogers was given the loan of an Otter (U-1) aircraft. This aircraft could transport 12 men or 2,000 pounds of cargo. We also acquired a warehouse room on Tan Son Nhat airfield for storage of our supplies.

The officers and men went to about seven different units and scrounged (and maybe did a little bribing) jungle boots and tropical fatigues.

Sgt. Sandoval, among the many items that he and the men acquired were five large refrigerator/freezers, 13 electric water coolers, plus two 65-cubic-foot refrigerators for the mess hall. Plus they stole an American Flag, Gold fringe and all from some headquarters office. All this was loaded on the Otter and sent north.

Capt. Rogers was making a round trip to Hue Phu Bai every few days transporting the loot to our company headquarters.

On 30 June 1965 the company was issued five (5) L-19 F MODEL aircraft, and the Company Commander and four of the other pilots flew up to our new home--Hue Phu Bai airfield. I stayed in Saigon in charge of the remainder of the advance party for a few more days until they were able to fly up to Hue in the Otter, then I picked up an aircraft and flew up to Hue.

When I arrived at Hue Phu Bai, the rest of the company had arrived from the states and was at work building the defensive perimeter around the company area.

This was the middle of summer in the near tropics and the temperature would hit at least 110 degrees during the day. We could only drink water from the leister bag, which was a canvas bag that kept the water a little cooler. At night we could then have a cold drink.

The enlisted men filled sand bags, (no shortage of sand) and constructed bunkers, and the officers strung the concertina wire (and this was a miserable job, we looked like we had been in a fight with a wildcat when the job was done.) Concertina wire is barbed wire in coils. We laid two coils side by side and the third coil on top to form a pyramid, then tied the coils together with wire.

Our company area was located next to the airfield parking ramp, and was a sand pile. We were housed in squad tents (about 40 feet long and 15 feet wide) with concrete floors. We had metal buildings for the mess hall, washhouse and a pit latrine...

There were also two smaller tents, one for Company Headquarters and one for Operations.

Later as we learned to work the supply and maintenance systems we had flush toilets installed and grass sod laid around the tents. We scrounged cargo parachutes to line the tents and with overhead fans we were ready to fight the war in comfort. Later on we sand-bagged a wall about three feet high around all the tents as protection.

Plus the company had the best mess hall in I Corps, and our biggest problem was keeping the number of Marines (they were eating canned food and field rations, and we ate steak) in the chow line down to a manageable level.

Enough about the company area for now.

The sector with the most combat action at this time was Quang Ngai province, the location of the 2nd ARVN Infantry Division, and the marines at Chu Lai. As the senior platoon leader my platoon was assigned to that location. Ah yes, Quang Ngai the garden spot of Viet Nam.

After the Company Commander worked out the support details with I Corps Commander (Vietnamese) and Corps Senior Advisor (American), Major Curry, the Company Commander, and I flew down to Quang Ngai and met with the Second Division Commander (Vietnamese) and the Division Senior Advisor (American.) This meeting was to work out the details of our support to the division, and the logistics of housing, mess, and our support of the platoon by the division and the advisory group.

My platoon was the first 1st platoon of three platoons in the company. We had eight O1-F single engine, two-seat aircraft, manufactured by the Cessna Aircraft Company of Wichita, Kansas, with eight pilots, eight maintenance crew chiefs, a Platoon Sergeant and myself. The pilots were a mix of ranks from 2nd Lieutenant to Captain and from just out of flight school to up to seven years of experience. All of the crew chiefs were young, most just out of the maintenance school at Fort Rucker, Alabama. Each crew chief had an excellent tool kit and was armed with an M-15 rifle. The pilots were armed with a .45 caliber automatic pistol and an M-15 rifle.

The platoon with eight aircraft supported the 2nd Vietnamese Infantry Division, which was in Quang Tri and Quang Ngai provinces. The United States Marines located at Chu Lai conducted ground and air operations in the two above- mentioned provinces. We also had two Special Forces Camps located in the mountains that we flew reconnaissance missions for. And last we flew coastal reconnaissance missions with a naval officer and on occasion controlled naval gunfire. We had a full plate.

In addition to all of the above, each pilot had two areas assigned to fly reconnaissance over, weather and the tactical situation permitting. One area was on the coastal plain, and the other was in the western mountains of our two assigned provinces. For a better understanding of this program read pages 3,4,5,6 of the 220th unit history.

When we arrived the only shelter on the airfield was a small roof for the Vietnamese to get out of the sun or rain. There were two CONEX (8’ x 8’ X 8’) containers that were being used by the two army 0-1 pilots from the 73rd Aviation (assigned to my platoon) Company, and a helicopter crew. So, constructing us a ready room and a covered maintenance location became our building priority.

When the platoon first arrived at Quang Ngai, we found the airfield was a little over a mile from our living quarters and had an excellent runway of about 3,500 feet long and 75 feet wide that was paved with asphalt. This runway could handle C-47, C-123, and up to C-130 aircraft. It had an excellent parking ramp. And a fuel and ammunition dump on the West end of the ramp well away from the runway.

Capt. Richards was dispatched with a couple of cases of whiskey to Danang, to visit the Navy Seabees construction unit. He sent back (don’t ask me how he did it) a C-123 loaded with a large tent with a floor and side wall kit and enough lumber, nails and tin roofing to build the cantilever shelter for aircraft maintenance.

Lt. Thomas Batten, who grew up helping his father in construction, was the project manager. Of course we all worked when not flying, and the tent and hanger were finished in short order.

By this time we had put five Vietnamese refugees, who did not speak English, on our platoon payroll. These were laborers and we paid them with wood from the ammo crates and the last two gallons (it usually was polluted with water or rust) from the bottom of the 55-gallon drums we refueled the aircraft from. They were well paid.

Capt. Charles Welsh later had them dig us a latrine, laid the hole out, pointed down and pantomimed digging. About the time they starting digging we became involved in a hot action with the United States Marines (operation Starlight 18-23 August 1965) and it was only fly and sleep for all of us. Five days later he checked the latrine and the Vietnamese had dug down about twenty-five feet. It was a beautiful hole, very rectangular, plumb, and oh so deep. Charlie then had them fill it in to about ten feet deep. He then built a three-hole box, privacy screen and roof, and we were in business, the latest in outdoor toilets.

Now a bit about the platoons setup at Quang Ngai:

The second division headquarters and the advisory group were located in a Vietnamese fort dated from the 12th century. With what was either a moat or a deep ditch surrounding the fort, the inside of that was a low dirt mound that must have been much higher at one time. The moat/ditch was now dry and was full of concertina wire and mines were installed. The advisory group lived in a small area within the fort called "Kramer compound". Three 12-cylinder diesel generators that ran 24 hours a day supplied electric power for the entire fort.

Our living quarters were cement cinder block buildings with 12’ ceilings and tin roofs. The openings were covered with screen wire, no glass windows, just shutters. There was a long covered open walkway down one side with the rooms opening off of it. There was a bath in the center of each building with toilet and showers, supplied with hot and cold running water. Each building had about 15 rooms.

All rooms were about 12’12’ and were for two men. The officers and sergeants had a refrigerator in their rooms and wall lockers were in all rooms. Each room had a "house woman" who washed and ironed our clothes by hand, polished boots, made beds and did general cleaning. This cost each person $7.50 US dollars per month.

We paid our "house woman" extra to keep us supplied with pineapples and limes. All of the "house women" were vetted by the Vietnamese Army and were the widows of military personal.

There was a small post exchange for smokes, whisky, and personal items, and a mess hall with Vietnamese cooks. The food was not the best; duck eggs for breakfast, sea salt (gray) with sand in it are two of the items we had to contend with. But it was cheap and we had plenty of it.

The club was for all ranks, and usually had cold beer, plenty of whisky, but sometimes ran out of coke to mix with the rum, always had soda and tonic to mix with the gin.

THE FLYING:

When we arrived in Quang Ngai it was the height of summer, with temperatures up to 105degrees and it seemed the humidity was 100 percent. Of course the only air conditioning was in our little club, so it was sweat and bear it. However, the weather for the most part was clear, and we could climb up to 4,000 feet and cool off on occasion. This clear flying weather gave us the opportunity to learn the country and the different landing strips in our area.

Little did we know the worst was yet to come; the monsoon that lasted from September to December. The monsoon at Quang Ngai would drop about 80 inches of rain in those months with most coming in October and November. We still received a lot of rain in December and in January it started tapering off. The temperate would drop to about 65 degrees and the humidity was so high our clothes and boots would mildew if not keep in a locker and with a light bulb left on at all times to keep it dry.

The flying during the monsoon was the worst any of us had ever known. We were flying some missions with solid cloud bases at 200 feet and forward visibility of less than one half mile, and this while moving at 105 miles per hour. Our only saving grace was that there were no high-tension electric lines and no high buildings, plus we were doing most of our flying over the coastal plain. And if we got disoriented we could fly east to the ocean. As for flying back to the Special Forces Camps and recon in the mountains, we just had to wait for a break in the weather.

From July 1965 to April 1966 the platoon lost three aircraft, one to combat with both the pilot and observer killed and two aircraft wrecked by the same pilot because of not following the correct flight or landing procedures.

We ruined three engines by following the "correct" procedure for our engine air filters by keeping them dry. After that we dipped the filters in a gas and oil mix and changed them after every mission. Several of the engines were using so much oil that we would fly back after a long mission at low speed so the aircraft would be in a nose high attitude. That way the oil in the oil pan would drain to the sump

so the oil pump would have enough oil to pump.

Since the Viet Cong did not much care for our flying over them, they would shoot at us but not hitting us too often at first. Then as the war progressed they got better at leading the aircraft and started hitting us more often. This caused us to frequently fly in a "slip" that is the nose of the aircraft would be at an angle to the actual flight path over the ground. Thereby we hoped they would lead the nose and the round would be passing to the side of the aircraft.

We worked out that the best altitude for both observing and safety was 800 feet above the ground. This was fine for the coastal plain but in the mountains and deep valleys, flying the trails that were the entry into our part of South Viet Nam from the Ho Chi Min system of roads and trails from North Viet Nam to the south, we were quite often down in the tree tops. Yes, occasionally we would bring small limbs and leaves in our landing gear back to the airfield.

On the coastal plain we flew single-ship missions, but back in the hills we always flew two-ship missions for safety in the event one ship went down. The way we flew the mission one ship would be down right on top of the trees following a trail and the second ship would be about one hundred feet higher and back just enough to keep the low aircraft in sight. That way we would be on the people using the trail before they could hear us. If we had an observer we could trust, he had a smoke grenade with the pin pulled ready to fire and holding the "Spoon" down and always holding it outside the aircraft. When a target was spotted the pilot would tell him to drop the smoke grenade to locate the target for the trail aircraft that would start climbing to call for an air strike.

We had worked so much with the marines that they would let us control their fighters. When they arrived on station we would mark the target with a white phosphorous rocket, and then control the strike. We used the Marines for the simple reason the Air force wanted their own controllers to work the target and that took time, then again, their fighters may not be available. This was total bull s---, we found seventy five percent or better of the targets and they wanted the credit. Plus we enjoyed working with the Marines and their observers, and they always had fighters on station or five-minute alert.

And so it went from July 1965 to 1 March 1966 when I received orders to report to company headquarters at Hue Phu Bai and assume the job of company S-4. This job entailed everything from being motor maintenance officer, test-flying aircraft just out of repair, (Chief Warrant officer Benny was in charge of aircraft maintenance) and insect and rodent control, supply and mess officer. Almost every job that was not command or operations was mine. I was now the third-senior captain in the company and that was the third-senior captain’s job in our company.

About 1 April 1966 I sent a request to Department of the Army asking that I be reassigned directly from Viet Nam to Germany after a thirty day leave.

I cannot locate the orders that transferred me back to the states, but I should have arrived back at Travis Air Force on or shortly after 20 June 1966. From Travis Air Force Base I took a bus to San Francisco and a plane to Atlanta. Of course my request for a European assignment went by the way. I was assigned to Fort Rucker, Alabama, then the orders were changed sending me to Fort Stewart, Georgia.

And then that great day 29 June 1966, I was promoted to Major. A field grade officer at last.

When I checked in to Fort Stewart, I was assigned on-post housing (a rather nice duplex), and was given the post tag number of "13", which on a larger post would have been the tag number for a full Colonel.

My job at Fort Stewart was to be Commander of "A" flight. I would be in charge of an assistant flight commander, usually six flight instructors, and up to twenty-four students who were in the second "B" phase of their flight training. At this point the students had approximately fifty hours of flight training and had soloed. More about the student flight training later.

Before starting to train students I had to go back to Fort Rucker to attend a three-week flight instruction course. So it was drive to Rucker on Sunday, train, then back to Stewart after flying on Friday, a distance on about 125 miles each way.

After completion of the flight instructor training, we were told that the "B" phase at Fort Rucker was not yet ready to be transferred to Stewart and we were to transition helicopter pilots into fixed wing (L-19) aircraft. This lasted for a month or two and then we received our "B" phase students.

This was in 1966 the second year of the troop buildup in Viet Nam, and the demand for aviation units had depleted units all over the world of pilots, and the army was desperate for more. If any Officer or Warrant Officer had met the requirements to enter the course it became almost impossible to "wash", (discharge) them out of flight training. Lord knows we tried, and the best we could do is set them back a class to receive more training.

The four training flight commanders fought this and we lost. The army needed pilots, so we gave our students the best training we could.

We knew that about half of the students were below standard in both flight proficiency and thinking under pressure, but we had no choice but to pass them up to the next ("C") phase of training. Woody Woodhurst received a letter from Major Schmale who was now the commanding officer of the 220th that he had to set up a 100-hour training course for some of the replacement pilots before he could release them to fly solo combat missions.

Fort Stewart is set in the middle of the South Georgia pinewoods. The small town on Hinesville is just outside the main gate and beyond that--pine trees. Savannah is about forty-five minutes driving time away and that is the place to escape from the army and the pines.

For about nine months after returning from Viet Nam I felt I was addicted to adrenalin. After flying combat missions and commanding the platoon at Quang Ngai life was now predictable, slow, and extremely dull. I fought this in some measure by (1) buying a 1960 Triumph TR-3 that needed rebuilding and working on it; (2) I started oil painting classes in Hinesville; and (3) spending time in Savannah in the museums, walking in the garden district, and sitting and reading. The restlessness eventually passed.

Fort Stewart became one of the best duty stations with good swimming pools, handball courts, and good flying weather most of the year.

William E. Everett

Catkiller 16